On March 24, 2020, Professor Padmanabhan Balaram found himself facing the same question facing so many other instructors around the world: how to move his course online. That day, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a 21 day national lockdown to combat the spread of the novel coronavirus. Prof. Balaram’s “Biochemical Curiosities” class at the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bengaluru, Karnataka had to go remote.

Together with his co-instructor, Prof. Balaram came up with a new assignment for their students. Rather than discuss examples of “curious molecules,” as they had been doing before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the students would review the existing scientific literature on various topics related to the coronavirus.

Professor Pandmanabhan Balaram at a lectern.

Indian Institute of Science, main building.

As he sifted through scientific journals, Prof. Balaram started to develop research questions of his own. A biochemist by training, who spent 41 years as a faculty member in the Molecular Biophysics Unit of the Indian Institute of Science, serving as Director from 2005 until his retirement in 2014, Balaram naturally became interested in the biochemistry of the coronavirus. And as a self-described “indiscriminate reader, who easily gets diverted from the task at hand,” he wound up reading several early papers about the coronavirus.

One name in particular stood out to him: Dr. Dorothy Hamre, a virologist and infectious disease specialist at the University of Chicago. In 1965, Hamre and colleagues in the Department of Medicine identified a new viral strain, 229E, which appeared to cause respiratory illness in humans—a coronavirus.

While Hamre’s published works were readily accessible through PubMed and Google Scholar, the scientist herself remained a mystery.

“I like to associate faces to names and quickly realized that here was a scientist whose work was important,” Balaram told Archivist for Discovery Sam(antha) Meier over email, “but every Dorothy Hamre image I encountered on Google Images belonged to someone different. At this point, it became a challenge, of sorts, to trace authentic photographs and also to learn about her life and work.”

Stumped, Prof. Balaram shared his interest in Dr. Hamre with his son, Aditya Balaram, a graduate student currently studying in the United States. The younger Balaram began obsessively searching the internet for a photograph of Hamre. After several different unsuccessful keyword combinations, he finally got a relevant hit: the Alexander Brownlee Collection (now re-titled the Dorothy Hamre and Kenneth Alexander Brownlee Photographs) at Cline Library’s Special Collections & Archives (SCA).

Reading through the biographical note, which stated that Dorothy Hamre earned her PhD in virology in 1941, working as a bacteriologist and research associate at the Squibb Institute of Medical Research before marrying British-born statistician Kenneth Alexander Brownlee in 1949 and joining the faculty of the University of Chicago in 1952, the elder Balaram became convinced that he finally had a lead. In late April, Prof. Balaram emailed SCA to ask whether the Brownlee collection contained any photographs of Hamre and if he could access copies of them. He and his son desperately wanted to put a face to a name.

Luckily, SCA staff were able to help. Over 100 images from the Brownlee collection were already available online through Cline Library’s Digital Collections. They had been digitized by SCA staff back in the late 1990s, a few years after the photographs were donated to Cline Library in 1993.

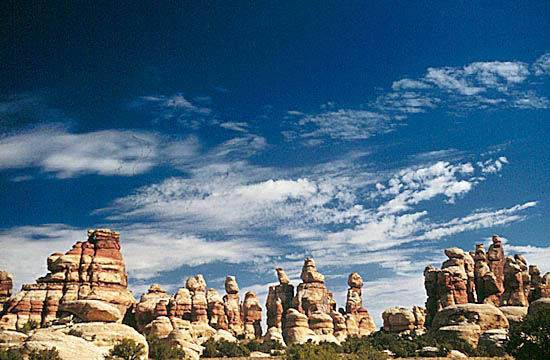

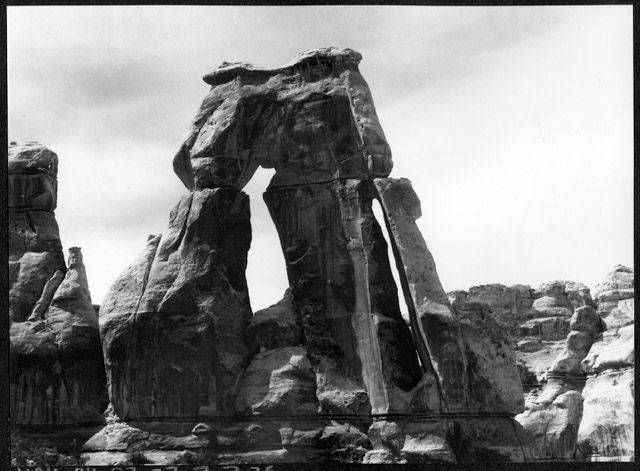

But when archivist Sam Meier reviewed these images, Dorothy Hamre was noticeably absent. Most of the photographs selected for digitization were scenic landscapes, river rafting shots, and various national parks and monuments across Utah, Arizona, and Colorado.

However, the finding aid indicated that the collection included several portraits of Dorothy Hamre and her husband K. Alexander Brownlee. The Archivist for Digital Programs, Kelly Phillips, and Meier began brainstorming ways to digitize these images without consistent access to their equipment, since most SCA staff are and were working remotely at the time.

As the two archivists worked together to figure out a solution, Meier sought to answer a new question from Prof. Balaram: why had Hamre and Brownlee’s photographs wound up in Flagstaff, Arizona in the first place?

Reading carefully through SCA’s documentation, Meier discovered that Hamre and Brownlee’s ties to the American Southwest dated back to the early 1950s. In the late 1960s, Hamre and Brownlee retired to Ouray, Colorado, where they spent the rest of their life together before Hamre’s death in 1989. The photographs donated to SCA largely depicted recreational activities the couple enjoyed throughout their time back east and out west: river rafting, Jeeping, hiking, and other outdoor adventures.

NAU.PH.93.37.2.5.2

NAU.PH.93.37.R0.16

In SCA’s documentation, Meier found an obituary for Brownlee and a photocopied excerpt from the 1984 book San Juan Country by Thomas Melvin Griffiths which described the Brownlees’ idyllic retirement. She also determined Hamre’s likely death date using information from the Ouray County Colorado GenWeb project.

Perhaps most importantly, a careful review of the documents revealed that many of the photographs in the “Brownlee collection” were actually likely the work of Dr. Dorothy Hamre. A close friend of the couple remarked in a 1991 letter to Cline Library, “Dorothy’s Leica 35mm photography and printing were superb, in my opinion rivaling the work of Ansel Adams.”

The archivist provided copies of these published materials to Prof. Balaram and updated the finding aid accordingly.

Prof. Balaram was delighted by the new information. He drew upon all he had learned from his interactions with Special Collections & Archives to write an article titled “Discoverer of coronavirus” for the May 22, 2020 issue of the Indian magazine Frontline. The magazine made his article their cover story.

Dorothy Hamre spent much of her life working on infectious diseases and discovered the coronavirus. As a woman building a scientific career in the days of the Great Depression and the Second World War, she must have been gifted with both imagination and resilience. She must have honed her experimental skills in the hard crucible of infectious disease laboratories. As the coronavirus rampages across continents, Dorothy Hamre emerges as a distant and anonymous presence. As the archives in Arizona are locked down, the virus will decide when we get to see an image of its discoverer.

–P. Balaram, “Discoverer of coronavirus,” Frontline, accessed online May 19, 2020.

Meanwhile, despite COVID-19 related limitations, SCA staff continued their work. Kelly Phillips digitized several images of Hamre using the department’s Imacon film scanner, working closely with Meier to make those images available online through Digital Collections. On May 8, the archivists wrote to Prof. Balaram to let him know that he could now see Dr. Dorothy Hamre’s face. He was “hugely delighted” to hear the news.

Based on these photographs, Prof. Balaram published a second article in Frontline, titled “Putting a face to Dorothy Hamre, the experimental scientist who discovered the coronavirus.” In the article, he thanked Phillips and Meier for their hard work in addition to providing updates on other information he had found about Dr. Dorothy Hamre.

Special Collections & Archives staff are now collaborating with colleagues at the Ouray County Historical Society to share images of Brownlee and Hamre’s life in Ouray, as well as any information gathered about their lives.

Prof. Balaram’s research continues. There is still much to learn about Dr. Dorothy Hamre, from her exact place and date of birth and death to the details of her scientific career. Her role in the discovery of the coronavirus remains less well-known than the contributions of her peers, despite the fact that other scientists like David Tyrell and June Almeida drew upon her early work with 229E.

For now, though, Professor Balaram is excited by the progress he has made, thanks to archivists around the world.

My interactions with Special Collections & Archives have really been the high point of my attempt to highlight Dorothy Hamre’s role in the discovery of the coronavirus. I have also found it curious that sitting in my apartment in Bangalore, India, I have been able to connect the Ouray Historical Society, Ouray, Colorado to the Special Collections & Archives at the Cline Library, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona. It is a tribute to the power of the Internet that the road from Ouray to Flagstaff passes through Bangalore. It also seems to me that in some strange way the virus has led us to its discoverer, by turning the world upside down.

–P. Balaram, email to Samantha Meier, May 17, 2020.