|

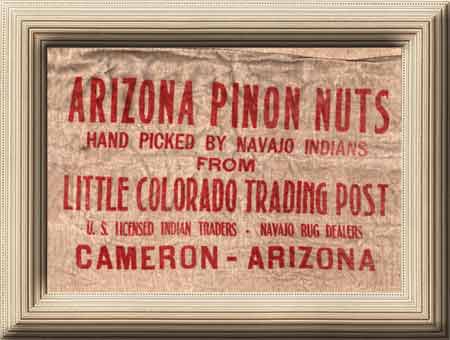

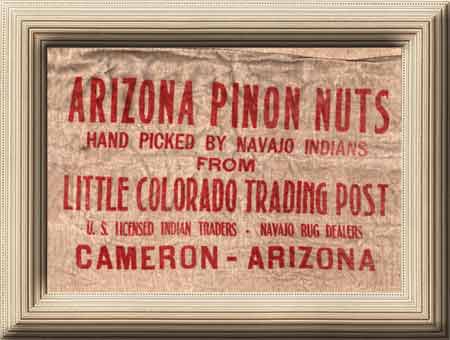

John W. Kennedy: Well, another sideline is the piñon business. The Ilfeld Company had a deal with a New York concern that handled edible nuts. Whenever there was a piñon crop, they would ship them to New York City, and they were consumed down there in the Lower East Side where the immigrant villages were--you know, tens of thousands of immigrants leaning out of the window, drinking cheap wine, and eating piñons. I saw in the Ilfeld book where they shipped a carload out of Las Vegas in 1906 at six cents a pound. Well, in later years all of eastern New Mexico would pick piñons for their own use, but not commercially. So it developed that whenever there was a crop, you only got production if it was where the Navajos could work. So every year we'd make a survey, and it would take about six weeks to cover all the southwest producing areas to see if there was a chance for a crop. In 1936, I was with the wholesale house and New York asked the manager if we'd make a survey. So the manager took me along and we were at Keams Canyon the first night, and we stayed at Cameron the next night. It was a four-day trip. I estimated maybe there'd be maybe 4 million pounds that year. So they formed this corporation in New York with the nut house, we'll say, and they borrowed a half-million dollars of call money, which was money you could get in at 2.0 or 2.25 percent. And we started buying piñons at twelve cents a pound, because they figured 4 million pounds, twelve cents, plus the freight, they could handle that. When the dust settled the next spring, there were 8 million pounds. And these piñons were stored in Santa Fe and Las Vegas, Magdalena, the wool warehouse here in Albuquerk, Gallup, and Flagstaff. And I went to Flagstaff four years later and shipped the last of those piñons. It took four years to clean up the crop, 'cause in those days, New York was the market. But after World War II, there were thousands of young fellows that spent their time in the Southwest and acquired a liking for piñon. So today if there's a crop, it takes over a million pounds just to satisfy the demand in the Southwest. That's how the piñon business evolved. We used to ship millions of pounds. After the Gallup Mercantile ceased, the New York people made me their agent out here, and I bought and shipped cargo for them. One year there was a big crop at the Grand Canyon. I went out and looked it over and figured I'd better get busy. So I went to Babbitt Brothers and said, "I'm an agent in the piñon business. This is what I can do." They figured I was infringing on their territory, and they said they weren't interested. So I hired a customer of mine in Phoenix. I had a summer stand on Highway 89 in the pines out north of Flagstaff. He had a trailer house and a little warehouse building and telephone and water and so forth. So he wanted to sell that, and I traded him rugs for it. I said, "Just leave it intact, I want to use it where it is." So I hired Hugh Lee, and he got on the radio as "Piñon Charlie" and announced that he was buyin' piñons at that stand. We shipped fourteen carloads out of Flagstaff. I went out every Thursday and shipped a 60,000-pound car. I could see that the market was getting out of hand so I went to him one day and said, "Shut this thing down," because I made the trip and I figured there were 3,000 Indians pickin' twenty pounds a day out there. So we shut it down, and I still had to go into storage with three carloads, which is dynamite, because they shrink in weight. The market is uncertain. But I finally sold 'em the next spring and got out from under it without taking a loss. But I've had every lesson in piñons ... (laughter) Underhill: We've been told it's a very volatile market. John D.: You know, he's pretty modest in what he did, because nobody in the piñon business did anything without checking with him first--nobody--the traders, the buyers. He could drive along at sixty miles an hour and tell you what the crop was. John W.: You'd see the cones glistening on the tree, and then you'd stop and see if they were gonna blight, or if they were gonna mature properly. There are certain areas that are very good. Grand Canyon is a marvelous area. Shonto is another big area. Pyatown-Quemado [phonetic spelling] is another huge area. This year they had a rather general crop. I've been out of touch with it for several years now, but they apparently had piñons at Thoreau and that area, and then down south at Pyatown and Mt. Taylor, and up in the Tierra Aguarilla and Cuba--up in that country they had a big crop. John D.: There was also a system he developed where the traders could call in every Monday and get a price that would last for a week, and they were protected, because of the volatility of the market, you know. So he would protect them for a week. He said, "Okay, I will guarantee you this price." Then I would take off in a truck on Monday, and every day--there were a lot of days I would load 20,000 pounds, come home, unload 20,000 pounds, get up in the morning, go do the same thing. And when we showed up, the traders knew they were protected on the price, because they had been given a price. And if the price dropped, we took the loss. And so we had to hurry and buy, hurry and load, hurry and unload, hurry and ship. Everything was hurry, hurry, hurry, because they were shrinking 10 percent in six weeks. John W.: The thing that ruined the business, though, was that guarantee, because in scarce years when there was a limited crop, the trader knew his guarantee, but the first guy along that offered another penny, bought the piñons. So you'd send your truck out to pick up your piñons, and no, they didn't have any. So your guarantee cost you money in the bad years. That's when I got out of the piñon business, because traders with piñons are like Klondike gold-seekers. They get a gold fever and they become changed individuals. They will change their tactics and their ethics, all over the price of a damned sack of piñons! (laughs) John D.: It was one of the later years, I remember we were debating on whether or not to get in it, so we were sitting there talking and Mom said, "You know, you guys...." The thing we were debating was first of all the amount of energy it takes to do it, and especially loading and unloading 20,000 pounds a day by myself. So that's 40,000 pounds in a day, you know. And we're sitting there talking about all the work it is and everything else, and Mom said, "You know, you guys are like the firehouse dog. When the bell rings, you're gonna run." (laughter) And we did…. Last year when we went into the mall--I had a retail store in the

mall, in Gallup, the Rio West Mall. I went to the mall people

and said, "Look, if you'll give me a space to buy piñons...."

And they didn't know what piñons were. So anyway, we

went ahead and did it, and we knew the crop was over by Flagstaff,

so we got on the Harry Billy Show in Holbrook and said, "Bring your

piñons to the Rio West Mall in Gallup." And they brought

us about a quarter of a million pounds, and the mall people were

just.... And all the shopping carts in the mall were lined

up, all these people with all their flour sacks. Then we put

'em into another place, and on Sunday we'd have an eighteen-wheeler

come in, and we'd haul 'em out. It was all cash business.

It was a great thing for the mall that year, because as soon as

they got the money, they went to all the stores in the mall.

It was a great, great thing for the economy anytime there was a

good piñon crop. ***

The other thing I want to talk about is the piñon business….One of my greatest triumphs was this same Fred Cavigia [phonetic spelling]that I talked about earlier, always had plenty of money, and he always had a willingness.... He's different than a lot of people that have made a lot of money in Gallup. He fed it back to the community and he's always been willing to help people get along. I figured out one year--I think it was 1966--that there was a limited crop of piñons, and the price has always been controlled by Syrian dealers in New York, Los Angeles, and the Azars from El Paso, Texas, were always right in cahoots with these Syrian fellows who controlled the market. I told Fred--and I forget who was the Navajo tribal chairman--but I told him, and I thought between what I could buy direct from the Indians, and what J. B., my brother, could buy at Yah-Tah-Hey, we could buy a big part of the crop. And the Indians had never got a guarantee of a flat dollar a pound at that point. And so I went out and really looked at all the crop in the field, and I thought, "You know what I think? I think 200,000 pounds, tops, we'll have 'em all bought." So I talked Fred Cavigia into loanin' us the money, along with what we had, to buy virtually the whole crop. Everybody thought we'd go broke, because they didn't know we'd arranged for the money, and everybody thought, well, we'd never see it through. Well, 385,000 pounds later, we had 'em all bought, and we had Fred Cavigia's soda pop warehouse full of piñons. (laughs) We had these buyers in New York and San Francisco thumbin' their noses at us sayin', "We're ready to give you sixty cents a pound for 'em." And they just were tryin' to freeze us out, 'cause they thought they totally controlled the market. Well, the first thing I had to do then, because we had a lot of the government looking at the pure foods pressure, I had to fly back and buy--I found a machine that would air clean the piñons to where we could get across state lines without having a contaminated product. So Fred loaned me a few thousand dollars more. (chuckles) So then I called New York and nobody would even talk to me. And that was the principal user, was New York. So I said, "Well, the only way we're gonna do this...." I just loaded a car of piñons, 40,000 pounds, on the railroad, shipped it to New York, and I had this guy from Hollander Trading Company that said he would receive it. I got to New York, and those guys literally laughed at me, the traditional dealers. They said, "You're a dead duck. You can't do anything here." So I went to the guy from Hollander Trading Company and he said, "Joe, I can't buy 'em, these guys are too strong. But if you can prove to me that I can sell 'em, I'll play the game." So I was doin' a lot of business with this gal at the American Indian Art Center. Nora, I think, was her name. I went over and I took her to dinner and we got to talkin', and she said, "Joe, people want those. All the vending machines all around town. All the little stores, everybody's begging for piñons, and there just aren’t any." So before I left, I had this letter from the Navajo tribal chairman--I think it was Raymond Nakai -- I had a letter from him, of support, saying it was the first time the Navajos had been guaranteed that dollar a pound--because usually they'd force the price down to where they got as little as ten cents. So we had a buck a pound in this, plus the shrink, and we're in 'em probably at $1.35 at this point, and we've got a sixty-cent offer. So she says, "Why don't we start doin' some phone calls?" So we figured out this spiel to give all of these people. We made 350 phone calls to different people. After about a ten-day program of this, of her and I makin' these calls with this spiel, my friend from Hollander called up and he said, "Joe, I never got so damned many phone calls in all my life! Come on over, I've got a check for you for this load, and a surprise." When I got over there, he not only had a check for the first carload--we even gave him the price, and he was paying us $2.10 a pound, which gave us a nice profit. He was adding on some for himself, of course, which we had arranged in our telephone campaign when we were givin' 'em their price. And when I got over there, he had my check, and he had two tickets to Funny Girl, and that was when Barbra Steisand first was getting her start as an entertainer. So I got to see Barbra Steisand in her first major production of Funny Girl, which was great fun. Before I even left New York, Los Angeles called, Azar called, and I flew from New York to Los Angeles, and then from Los Angeles to El Paso. Within six months we had the whole crop sold, and Fred back to breathing normal! (laughter) |