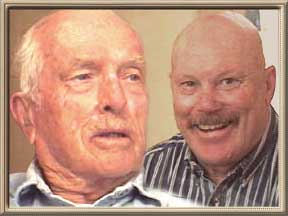

J.W. & J.D. Kennedy

Full Transcript in Text Format

John W.: My father was operating a general store at Guam, which is just…. this side of Gallup. Guam was quite a trading center back in 1909 and 1910. That was the end of the railroad, and the logging trains came out to Zuni Mountain to hit the main line there, so there was a good deal of train activity. My mother came in on the train to Albuquerk [Albuquerque, New Mexico], when I was born. As I tell people, there are two great things that happened in 1912: statehood, and I arrived. (laughter)

Hans Neumann, who later had the Gallup Mercantile Company in Gallup….

backed [my father] on a project to go into the Navajo country. So

in the spring of 1913 he took wagonloads of building materials and hauled

'em out to Salina, which was about thirty-five miles from Ganado, and

built the Salina Trading Post. He operated the store for two years,

1913 through 1915. He then…. bought the store at Chinle--Chinle

Trading Post there at the mouth of the canyon…. Then he sold it to Cozy

McSparron in January 1919. And I remember we crossed the mountain

in buckboards. A buckboard is a seat with four wheels pulled by

two horses. There was about eighteen inches of snow across the mountain.

We got into the old sawmill late at night. The next morning they

spent hours trying to get an old Republic truck started. They pulled

it all over the flat with six horses, finally got it started, and we got

down to Fort Defiance and stayed with Lewie Sabin that night. Then

the next day we went on into Gallup. So we had a three-day trip.

Today you can do it in about an hour and twenty minutes, so time has changed

quite a bit.

***

Underhill: What are your early memories of being at the

post at Salina? You were out there, you were fairly small then.

John W.: Yeah. I don't have any memories of Salina. I've gone back there many times. I do have early memories of Chinle. My mother refers to a place, an incident in her book. The three of us boys, the older brother and younger brother, we'd walk up the canyon and there was a place where as the winds blew, the sand sifted over the rim of the canyon. There was quite a large sand dune, and we used to go in there to play. This one day we came out of the canyon, and shortly thereafter, there was a massive flood came out. The waves were six foot high, and it was just a streak of luck that we were able to get out of there. Someone had their arm around us. Those floods used to occur because they didn't have the Wheatfields and Tsaile dams that they have now. So if there was a thunderburst up in the mountains, a couple of hours later there'd be this huge flood coming out of that canyon. I can remember vividly the hogan logs and dead burros and all the debris that washed down. The water came, swept into that curve there by the store, and we had taken all the rugs off of the floor because the water was beginning to come in on the floor of the house. We didn't have to move out, it subsided shortly after that.

Trading at Chinle was kind of an isolated thing at the time. If

you made a trip to town, it was an all-day trip. We'd leave at four

in the morning and drive all day long by way of Ganado and St. Michael's,

get into town about dark. They just had the two-track road, a wagon

road, to follow across that country at the time. There were no graded

roads at all.

Underhill: And "town" was Gallup?

John W.: Yeah, that was the main trade center for all of

the central reservation. Farmington was the trade center for the

northeast traders, and Flagstaff was the trade center for the western

traders.

Underhill: What were living conditions like at Chinle when

you were young?

John W.: Well, it's changed a great deal. Whenever

a salesman came by, or someone touring the country, and they had to stay

overnight, why, they stayed at our house, and we boys slept on the counter

over at the store. There were no facilities of any kind in Chinle

at that time. Later, Cozy built several cottages. When

I was selling for the wholesale house in the early forties, I always stayed

there. I'd go out and work all the way to Ganado one day, and down

to Chinle the next, and then back to Ganado and out to Sunrise and Dilkon

and White Cone the next day.

Underhill: So when you went to visit, you didn't sleep on

the counter, huh?

John W.: (chuckles) Things have changed. Chinle

now has three large motels, they have almost 300 rooms, I think, now,

for guests.

***

Underhill: What kind of man was Earl [Kennedy]?

John W.: Earl was.... Most of those guys were fairly conservative, except the younger one--he was a wild one. Earl had some of everything that he ever bought in the years he was at Lukachukai. One year a fellow who was traveling the reservation and picking up rugs for me and selling jewelry, came in and said, "Earl has a bunch of piñons." I had been shipping quantities of piñons for years. I had an outlet in New York that took millions of pounds. So we arranged to go out there with him in February or March--cold, miserable day, the snow was blowing. We weighed Earl's piñons, and I gave him a check for 'em and told him I'd have a truck pick 'em up in a few days.

We were havin' coffee in his kitchen, and I said, "Earl, where are all your rugs?" I was just probing. He said, "Well, you saw the stack in there by the flour in the wareroom." I said, "That's your dogs. Where are your rugs?"

After a while he got a key off the kitchen wall and we went out and opened up a pumphouse in the back yard and it was stacked solid with Navajo rugs--years and years of supply. It was a pumphouse as large as this room here. So we set an orange crate out in the back yard, put on our mackinaws, put an adding machine on the orange crate. He'd pull a rug out. "How much, Earl?" "Sixteen or fourteen or eighteen," whatever it was. He had his code on there, "H.O." We would kid him, "Earl, last time, 'H.O.' was fourteen. How come it's sixteen now?" (laughter) Finally he said, "I think I've sold enough stuff today," and the adding machine said $7,000 plus, and I was wondering what I was gonna use for money.

So I arranged to have a wholesale truck pick the rugs up a few days later. But there was a shortage of rugs at the time, and I let word out there in Gallup that I had these rugs, and within a week's time, Kirk Brothers and Woodard and Mercantile took the whole works. So in December that year, Earl was in Gallup and he told my friend, "You and John come out again. I'll have the coffee ready." So we went out and weighed rugs again, and it took three trips to clean him out before we got all the rugs out of that. I wish now--today you'd have a field day with those rugs, 'cause a lot of marvelous old designs.

But Earl.... One time my friend wanted some wedding baskets, which all the medicine men used, you know. And he said, "Earl, I've gotta have a few wedding baskets." And Earl said, "I don't know whether I can let you have any or not." But they went out to one of the barns, and he must have had 2,000 in there! (laughter) But he was that way. He saved a lot. And Walter is just like him.

I think of the time.... I used to get a lot of rugs from Russell Foutz when I had the wholesale house, and Russell liked to lead the parade with those traders up there. He said, "I've gotta have a new Cadillac." So I told the Cadillac dealer in Gallup, "I've got the rugs, and as I sell 'em, I'll just send the checks to you every month if you want to give him a Cadillac." So Russell got a Cadillac. So the next time I saw Walter Kennedy, he said, "Goddamn it, I want a Cadillac!" I said, "Well, what have you got, Walter?" We went in his vault, and he had all these shoe boxes of the dead pawn of every year he'd been there, twenty-some years. So I looked and I said, "Well, we can make a deal." So I'd get a box and look at it. "Oh, I can't let that go!" The next one, "I can't let that go!" I said, "Walter, for godsake, you wanted a Cadillac. Stop right here." And that ended the deal! (laughter)….

John D.: You know, I remember one of the things about Earl,

when we made those early trips, and he just had that little stack of rugs,

and some tourists came in and said, "Do you have any Navajo rugs?"

He said, "No." And there's the stack sittin' over there, so they're

standin' around. After a while they said, "Well, what about those?"

He said, "Oh, those are prayer rugs." "Really?!" They were

god-awful rugs. Like Dad said, they were the dog rugs. And

so pretty soon they're rootin' through 'em and everything else.

They walked out, and I remember we said "Earl, what the hell's a prayer

rug?" He says, "Those are rugs I'm just prayin' somebody'll come

by and buy." (laughter) From then on, anytime anybody ever

said, "I've got a prayer rug...." (laughter)

Underhill: Now, was this attitude toward tourists pervasive

among traders?

John W.: Well, so many of the traders, you know, they worked

all day long. It was hard work: they opened up in the morning

and it was a crash program until they could finally close their doors

sometime after dark. So they were always behind in their work, whether

it was stocking shelves or getting stuff out of the wareroom or whatever.

Well, when a tourist come along, they took up a lot of time, asking questions

and wanting to see everything. And while you're talking to one tourist,

you could wait on three or four Navajos. A lot of 'em, they held

back a lot when they were dealing with outsiders. Later on, as the

roads improved, they all got to where they'd like to have a tourist come

along and look at the rugs, but it took a few years to break 'em down.

***

John W.: ….Another sideline is the piñon business. The Ilfeld Company had a deal with a New York concern that handled edible nuts. Whenever there was a piñon crop, they would ship them to New York City, and they were consumed down there in the Lower East Side where the immigrant villages were--you know, tens of thousands of immigrants leaning out of the window, drinking cheap wine, and eating piñons. I saw in the Ilfeld book where they shipped a carload out of Las Vegas in 1906 at six cents a pound.

Well, in later years all of eastern New Mexico would pick piñons for their own use, but not commercially. So it developed that whenever there was a crop, you only got production if it was where the Navajos could work. So every year we'd make a survey, and it would take about six weeks to cover all the southwest producing areas to see if there was a chance for a crop. In 1936, I was with the wholesale house and New York asked the manager if we'd make a survey. So the manager took me along and we were at Keams Canyon the first night, and we stayed at Cameron the next night. It was a four-day trip. I estimated maybe there'd be maybe 4 million pounds that year.

So they formed this corporation in New York with the nut house, we'll say, and they borrowed a half-million dollars of call money, which was money you could get in at 2.0 or 2.25 percent. And we started buying piñons at twelve cents a pound, because they figured 4 million pounds, twelve cents, plus the freight, they could handle that. When the dust settled the next spring, there were 8 million pounds.

And these piñons were stored in Santa Fe and Las Vegas, Magdalena, the wool warehouse here in Albuquerk, Gallup, and Flagstaff. And I went to Flagstaff four years later and shipped the last of those piñons. It took four years to clean up the crop, 'cause in those days, New York was the market. But after World War II, there were thousands of young fellows that spent their time in the Southwest and acquired a liking for piñon. So today if there's a crop, it takes over a million pounds just to satisfy the demand in the Southwest. That's how the piñon business evolved. We used to ship millions of pounds. And after the Gallup Mercantile ceased, the New York people made me their agent out here, and I bought and shipped cargo for them.

One year there was a big crop at the Grand Canyon. I went out and looked it over and figured I'd better get busy. So I went to Babbitt Brothers and said, "I'm an agent in the piñon business. This is what I can do." They figured I was infringing on their territory, and they said they weren't interested.

So I hired a customer of mine in Phoenix. I had a summer stand on Highway 89 in the pines out north of Flagstaff. He had a trailer house and a little warehouse building and telephone and water and so forth. So he wanted to sell that, and I traded him rugs for it. I said, "Just leave it intact, I want to use it where it is." So I hired Hugh Lee, and he got on the radio as "Piñon Charlie" and announced that he was buyin' piñons at that stand. We shipped fourteen carloads out of Flagstaff. I went out every Thursday and shipped a 60,000-pound car.

I could see that the market was getting out of hand so I went to him

one day and said, "Shut this thing down," because I made the trip and

I figured there were 3,000 Indians pickin' twenty pounds a day out there.

So we shut it down, and I still had to go into storage with three carloads,

which is dynamite, because they shrink in weight. The market is

uncertain. But I finally sold 'em the next spring and got out from

under it without taking a loss. But I've had every lesson in piñons

__________. (laughter)

Underhill: We've been told it's a very volatile market.

John D.: You know, he's pretty modest in what he did, because

nobody in the piñon business did anything without checking with

him first--nobody--the traders, the buyers. He could drive along

at sixty miles an hour and tell you what the crop was.

John W.: You'd see the cones glistening on the tree, and

then you'd stop and see if they were gonna blight, or if they were gonna

mature properly. There are certain areas that are very good.…

John D.: There was also a system he developed where the

traders could call in every Monday and get a price that would last for

a week, and they were protected, because of the volatility of the market,

you know. So he would protect them for a week. He said, "Okay,

I will guarantee you this price." Then I would take off in a truck

on Monday, and every day--there were a lot of days I would load 20,000

pounds, come home, unload 20,000 pounds, get up in the morning, go do

the same thing. And when we showed up, the traders knew they were

protected on the price, because they had been given a price. And

if the price dropped, we took the loss. And so we had to hurry and

buy, hurry and load, hurry and unload, hurry and ship. Everything

was hurry, hurry, hurry, because they were shrinking 10 percent in six

weeks.

John W.: The thing that ruined the business, though, was

that guarantee, because in scarce years when there was a limited crop,

the trader knew his guarantee, but the first guy along that offered another

penny, bought the piñons. So you'd send your truck out to

pick up your piñons, and no, they didn't have any. So your

guarantee cost you money in the bad years. That's when I got out

of the piñon business, because traders with piñons are like

Klondike gold-seekers. They get a gold fever and they become changed

individuals….

John D.: It was one of the later years, I remember we were debating on whether or not to get in it, so we were sitting there talking and Mom said, "You know, you guys...." The thing we were debating was first of all the amount of energy it takes to do it, and especially loading and unloading 20,000 pounds a day by myself. So that's 40,000 pounds in a day, you know. And we're sitting there talking about all the work it is and everything else, and Mom said, "You know, you guys are like the firehouse dog. When the bell rings, you're gonna run." (laughter) And we did….

Last year when we went into the mall--I had a retail store in the mall, in Gallup, the Rio West Mall. I went to the mall people and said, "Look, if you'll give me a space to buy piñons...." And they didn't know what piñons were. So anyway, we went ahead and did it, and we knew the crop was over by Flagstaff, so we got on the Harry Billy Show in Holbrook and said, "Bring your piñons to the Rio West Mall in Gallup." And they brought us about a quarter of a million pounds, and the mall people were just.... And all the shopping carts in the mall were lined up, all these people with all their flour sacks. Then we put 'em into another place, and on Sunday we'd have an eighteen-wheeler come in, and we'd haul 'em out. It was all cash business. It was a great thing for the mall that year, because as soon as they got the money, they went to all the stores in the mall. It was a great, great thing for the economy anytime there was a good piñon crop.