![]()

|

Stella McGee Tanner: Going back to my husband: he was always a promoter with everything. When he was young, Grandpa was going to be gone for a week, and they had all this yard that had all kinds of rocks in it. She said, "I don't know what I'm going to do with that Chunky Tanner this summer. He's driving me crazy!" Grandpa said, "Leave that to me." So he called Chunky and he said, "See all these rocks out here? I want 'em all cleaned up. I'll give you twenty-five dollars to have this all cleaned up when I come back next week." Boy, that sounded like a lot of money to Chunk. He said, "Okay," and went a couple of days and he didn't do anything. Mother Tanner got after him. She said, "I thought you told your dad you were going to clean this all up." He said, "I am!" And she said, "Well, when?!" And he said, "Well, starting in the morning." And she said the next morning she was wakened at daylight, all this noise of shovels and wheelbarrows and kids a-hollerin'. She went outside and Chunk was in the middle of the yard, and he was directing all these other kids how to do everything. By night, he had it all done. He paid them so much, and he had the rest. (laughter) He was a promoter. That's why Chunk always had the kids movin' gravel. (laughter) My boys, if they'd get doin' something he didn't like, he'd say, "I want all this gravel out here moved over here." And they'd do it. And then he said, "When you get that done, you can go play." And so they'd do it, and they'd say, "Well, Dad, we got it all done." He'd say, "Okay, now smooth it out." (laughter) That's what kept 'em busy and learned 'em how to work.

***

JB Tanner: And after we were�I think I was two-and-a-half years old�. Anyway, they moved back up here and Progressive Mercantile put Dad out here at Montezuma Creek. And I was sick from the day, all that time I was in Phoenix, I just barely stayed alive.... At Montezuma Creek, there was a medicine man down there. Dad and Mom told him that I was born premature and all this and that, and he said, "I'll fix it." So he brought 'em a milk goat. He said, "Feed him this goat milk instead of whatever it is you're feedin' him, and within a month he'll be all right." And sure enough, it worked. So I guess that goat's milk was pretty powerful. But that's where they come from, Mesa, and was here [working] for this Progressive Mercantile down here at Fruitland. That was a wholesale warehouse. They owned several stores on the reservation, and they put various guys on it and give 'em a chance to buy 'em. Dad first went to Montezuma Creek and was there two years and done real well. Progressive Mercantile bought Tsaya, over here on the road to Crownpoint from Farmington. That's a paved road now, but back then it was just two tracks. They had 5,000-6,000 head of sheep and a trading post, and they wanted Dad to go out there and run, 'cause he had done so good at Montezuma Creek. My dad, as I started to go with him, I was so small that it was hard--he

didn't want me to be self-conscious that I couldn't do anything.

So he managed to come up with some of the darnedest jobs. He'd just

come up and tell me to go do this, whatever it was. He knew I'd

figure out how to do it. *** Jack Manning: My dad worked for Bruce Bernard Trading Company. He started to work there in about probably 1927, 1928, and worked there basically all of his life�. The owner was Bruce Bernard. He was a gentleman that'd come out here from back East, back in Kentucky, and liked it. If I remember right, he'd kind of received an inheritance and he bought this trading post at that time. For that area of the reservation, it was probably one of the larger trading posts. He built it up. He did an awful lot for the Navajo people in regards to their sheep. He raised Rambouillets, and they had so much trouble with the Rambouillet rams, of their horns being so close to their head, that they would get worms in their head, and they would lose them. Over a period of years, he bred them to where the horns were three and four inches away from their head. And he had some beautiful, beautiful sheep. If they couldn't afford to buy one, he would just loan 'em rams. It certainly improved the wool off the Navajo sheep in that area of the reservation. Of course the trading post, he just operated it like any other�bought

livestock. Until after World War II, there wasn't hardly any money,

everything was the barter system. In the spring you bought the wool

and they paid their bills, and in the fall they brought their lambs and

calves and paid the bills again. I can remember my dad telling about

one month, I think it was the month of February, the whole month they

did less than $100 cash business. In today's world, that's a little

strange.

*** Mary May Bailey: When I first arrived at Pinon, I was about three years old. And then we had a car, which was an old Dodge, and that's my first memory, is being asleep in the front seat between Mother and Daddy, and hearing that car gear down and gear down, like they used to, and then come to a stop, and seeing my dad take off his shoes and socks and his pants, and then we could see him go down to the wash and wade and see if he could find a rock bottom or something we could cross on. And if not, then he came back and he said, "All go to sleep, we're here for the night." And we'd have to wait 'til the wash went down, to cross. And that was either the Polacca Wash, or one of those coming in that area, because we were always around the Hopis. But it was some exciting times. Of course we didn't get any mail, much; and no fresh groceries. But occasionally they would send them out from Flagstaff or Winslow or Holbrook on the mail route. So we did get some connection. Lorenzo Hubbell brought Daddy a wet battery radio-one of the first ones-but they could never get it to work. So that was out. No telephone. My father had an abscessed wisdom tooth, and he was suffering the agonies of the damned with that thing. He heard of a doctor, he thought, that was at Keams Canyon. So the doctor turned out to be a stockman for the United States government, and all he had was one pair of forceps. So he pulled and yanked and pulled and yanked--now, with that infected--and got it out. And then he bathed it in.... What was it? Oh, shoot! It was some kind of an acid, but it wasn't an antiseptic. And oh, he had the sorest mouth and throat for a long time. Mother fed him egg whites beaten with sugar in it, to keep him goin'. But at least he didn't have a toothache! Now, my uncle Barney, who this started out with, had a toothache when he was rounding up cattle, getting ready to bring 'em in here to ship from Winslow. And it was hurting him very badly, and he knew there was no dentist here and none anywhere around. So he heated a wire, red hot, and found the hole and stuck it in there and cauterized it. Well, when you hurt bad enough to do that, you hurt! But I've often thought how strong a people these had to be…. There was no place.... We were eighty miles from any railhead from anyplace, mainly. And there wasn't much communication among people. They just didn't travel around. We did go to Ganado, finally, and meet the elder Hubbells. And that was the first electric refrigerator I ever saw. And my, how marvelous to make ice! (chuckles)

*** Stella McGee Tanner: We went down there [to Montezuma Creek ] in 1925, in June. That was the end of nowhere. There was no road, only just about like the ones we traveled in to go into Springdale. Got down there, and then had to turn the Model "T" back to Willard, and he drove it back. He went down and followed us down. Never seen a white person then for eight months. Just sit right there. The store was in pretty bad shape, but my husband was a real good Navajo talker, and he really built it up. We got 1,400 head of lambs that first fall, in 1926. He bought more lambs that year than he did before. The Paiute Indians were down there at that time, and I remember how frightened I was of them at first. But you know, those Indians became my best friends, and they're the ones that really taught me a little bit. I'd follow Chunk around and I'd say, "What did he say? What did he say?" And he said, "Oh, get this girl to tell you what they said." That's how you picked up the language, and I got to where I could tell 'em how much stuff was, and just gradually learned the language�. But of course my husband was a very fluent speaker, just like his father was. So we were there for two lamb seasons. That's how they did way back there. They'd have two pay days: wool season and lamb season. And the traders would carry 'em on the books. And then when they'd make a rug, they didn't make these real fancy rugs then, but they'd bring 'em in and the trader would tell 'em how much they were worth, you know, and write it down on a paper bag. They'd buy one thing at a time. And after they'd buy one thing, why, they'd have to know how much they had left. And then it would just take 'em all day to trade out that rug, because they liked to come into the trading post in their wagons�. And we used to buy the rugs by the pound back then, because they didn't

have the real fancy designs. They had some, but not real good ones.

But in the fall of 1926, we went out with the lambs. That's the

only time we left the trading post, is when we delivered the lambs into

Farmington, New Mexico. *** Jewel McGee: When I first got out of school, I went out to a little ol' place out north. They called it Tsaile. I herded sheep and worked in the store. Then I went from there to Red Mesa�Arizona down here�and I worked there for, oh, I don't know, two years, probably, and then I went over to Red Rock, Arizona. You know where that is, there? Lukachukai. That's where I ended up owning. I went in with my uncle. I started to work for him, and then I bought him out and owned it for a long time�. Cole: Do you speak Navajo? McGee: Oh, yes. Cole: How long did it take you to learn? McGee: Never did get it all learned! (laughter) I don't think anybody ever does. Anybody that really learns to talk fluent Navajo has gotta be raised there�. You�d go in the store, and sure I learned Indian, and I learned the store talk, but when you get out any other places, why, I get lost pretty quick. Cole: So how did you communicate while you were learning the store language? McGee: (points with finger) By pointing. (chuckles) Pretty soon, he'd say the name of the can of tomatoes, and you had to learn to remember that. And you just gradually pick it up�. Oh, I don't know, I guess after a year or two when the Indians got to comin' in more and tradin' with you, why, you was accepted more. They'd come in and visit and stuff like that. You'd just have to feel like you're kinda like one of 'em�. We used to credit the stockmen and everybody like that. We'd give them credit accounts, and then we'd buy their lambs and their wool. Of course we always had their rugs. It was an item with 'em that we marketed and sold for 'em�bought 'em and sold 'em�. It was a good stock country out there, you know, between those creeks

and mountains and the red wood. There was lots of stock in there.

I used to buy about 4,000 lambs and 400 bags of wool every year.

Talking about big bags, not little ones. *** Ruth Bloomfield McGee: My mother and dad were having a hard time at the trading post because Daddy had bought up a lot of sheep from all of the other Indian traders, and they trailed them to Gallup. They didn't haul them, they had to trail them. And when they got there�they were contracted�and when they got there, the contractor couldn't honor the contract, and so they just had the sheep and it was storming, and they just lost all the sheep. And Dad was responsible, because he'd bought up all of the other trading posts that were close. So he was in financial trouble, and so he went to work for the government, left the store for Vernon, my brother, to run. What he was doing�. they were using Navajo labor�. building reservoirs

and that kind of work, and Daddy was the supervisor over that. And

they had stopped at the Red Mesa Trading Post, because that was an area

where they were working part of the time, and met my husband [Roscoe]

and Jewel, who you visited with, and they liked the young man, and Daddy

told him, "Well, I've got three pretty daughters. I would like you

to meet them." (laughter)�. *** Stella McGee Tanner: After about the third or fourth year, the grass began to�we didn't have

any storm, and the sheep began to have trouble with their feed and everything.

I think it was about in 1929, I remember my husband saying, "All these

expensive sheep...." He paid eight dollars a head for 'em, when

we bought in. And then the lambs dropped down to three cents a pound

that year, in 1928 or 1929�delivered in Kansas City. (chuckles)

And so we began to really having to be�went really in debt, you know,

because we still owed a lot on the sheep. Then in 1932, why, the

ground�there wasn't any feed anywhere. So the government came in

and they had the traders, all of them, cut down�and the Navajos, too�on

all their herds, and they'd run 'em into these canyons and just slaughter

'em, because there was no feed for 'em. I'll never forget what a

terrible ordeal that was for my husband. It was hard on everybody.

*** Mary May Bailey: Oh, my, growin' up was fun! It was a bitter cold winter in 1930. Cattle froze standin' up. The chickens lost their feet. We lived out, and you could hear the train whistles from Holbrook. So [my father, Jot Stiles,] had to break ice all the time. They use a tripod. When these cattle would get so weak, they'd get down and they couldn't get back up. So they'd work with horses and put a tripod over the downed animal, and a strap underneath 'em, and try and raise 'em up. Well, they would be on the fight so badly, they'd come at that horse and gouge them, and that was probably enough to send 'em back down, so you did the whole thing over and over and over again. Before we could come to town, Daddy would say, "We might go to town today,

but don't get dressed yet." And he'd take boiling water and pour

over the manifold--whatever that is--and then he'd attach the horse to

the car, and they'd go around and around and around until the car would

start, and then we knew we were goin' to town. ***

Ruth Bloomfield McGee, reading from Roscoe McGee�s history:

I'll just read a little bit, this little part. "Times were real hard and no work and no money in 1933 and 1934. Jewel and I lived very carefully, even to what we ate, to make a go of it. We bought lambs from the Indians as soon as they came down off the mountain in October. In 1933 we paid four cents a pound for them. We bought about 500 head, and we drove them to Shiprock and sold them to Bruce Bernard at Shiprock for four and a half cents a pound. I think they averaged about $2.50 to $3.00 a head. Jewel trapped coyotes and bobcats and foxes and badgers all winter while I ran the store to help out. "In 1935 and 1936 and 1937, the government, under Franklin D. Roosevelt, started many public works programs. About all I knew very much about was that program that affected the Reservation and the Navajos. Navajos were given jobs with the BIA, bosses, supervision, developing springs, building reservoirs for stock water and all types of erosion control work. They would pay the Navajo $1.50 a day for hand labor, and if the Indian had a team and a scraper, they would pay them $3.50 a day...and they had to buy hay and oats for their horses out of this. "These programs saved the Navajos' and traders' lives. I don't think we could have made it otherwise, as sheep, goats, and cattle, and wool and mohair were hardly worth anything. We bought a few Navajo rugs and saddle blankets, but couldn't get very much for them. The government, during these years--1934, 1935, 1936, and 1937--carried forth a great reduction program, making Navajo stockmen sell their sheep, goats, cattle, and horses for give-away prices. And they had to sell them or go to jail. They paid $1.00 a head for sheep and goats, $5.00 for horses, and $7.50 for cows. These were supposed to have been hauled out and butchered to be eaten

or canned for food. Roads were poor and it was impossible to haul

all of them off the Reservation, so thousands were shot or killed and

dumped into washes or other places and left to rot."

*** Bob Bolton: There were no jobs. It was in 1934, right during the Depression. My dad was very fortunate to find a job. One of the things we always did, at that time there was a lot of rabbits and a lot of birds, and we hunted all the time. We had a .22 rifle, and my dad had five sons, and he gave the five of us a .22 for Christmas�. one rifle for five. It was a single-shot, and if you took a bullet, you had to bring something back. (laughter) �.And a lot of times, we would catch a rabbit or throw a rock at 'em, because they were quite plentiful, and then we would have an extra .22 shell! But it was a very difficult time. If it wouldn't have been for pinto beans and rabbits, I probably wouldn't be here. (laughs) *** Russell Foutz: [In high school] I was out there working at Teec Nos Pos. As we'd go into the store, it was connected to there. They were old rock buildings. I remember this first time that I was going from the store to�here come this great big bull snake which I got this close to, and then had to go over the top of it. They kept them in the wareroom to take the mice. There was very few checks, maybe.... at first there was only about one family that got a check there. There was very little money. We kept on the wool. We'd sell part of it, then we kept on the wool. Most of the furniture was made out of coffee crates�the Arbuckles Coffee Company. You did your own cooking. They had a cow. It was quite primitive in those days�. Ken Washburn, he was there. By the way, he wrote poetry at night, when he was a teenager, too .... right around the fire. That's when I was still in high school. He would write poetry and send it in to the Ladies Home Journal under a woman's name�he would put a fictitious name on it. A few pieces of his poetry was published. �. But right after that, the livestock began to dwindle on the reservation, and they call it the "John Collier days," when he brought in his sheep reduction program. It brought a lot of uprising on the reservation. Before that, some of the families had probably over a thousand head of livestock. And they were making them slaughter their goats and their sheep� I remember that my brother [Edwin Luff Foutz] who was one of the early

members of the Traders Association, was out at Teec Nos Pos right about

that time�. He died at Teec Nos Pos. There was an epidemic of meningitis

going around, and they didn't feel that they could close the store, that

that was the only source the Indians had of getting merchandise, or getting

help, or getting any word to the hospitals or anything. But even

though he run the store with no stove in it, and the windows and doors

open, he still contracted meningitis and died�. *** Jack Lee: �. at Two Grey Hills I was there alone, and at that time they were building that irrigation ditch from down the river, on the San Juan River down to Shiprock, and they went through an old ruin. They quarantined the whole valley 'cause it had spinal meningitis germs started. I was goin' to school over there, and workin' at Two Grey Hills. This gal died at Two Grey Hills, and the BIA doctor at Shiprock� I called him and I said, "Doc, what am I gonna do? That woman died from that disease in the spine." She was bent over like that. The muscles, I guess, tie up on 'em, I don't know. But she was an awful-lookin' thing. I said, "Doc, I think she has that damned disease that was quarantined." He said, "Oh, my God, I don't know what to do. It's so contagious! I'll tell you what, get some cotton gloves"�"we got some." I had some of those old brown gloves. And I got a pair of those. He said, "You go out there. Put something over your face, a towel or something over your face, and don't breath much. Don't get any closer than you have to, but you go ahead and bury her. And then when you get back to the store, get that damned wash tub out...." That's what we bathed in, an old galvanized tub. He said, "Fill that about half full of water. You got any Lysol?" I said, "Yeah, I got a bottle of Lysol, quart size." He said, "Pour half of that in." I guess it was only about maybe three or four gallons of water in that damned tub. I poured that whole works in there! Stirred it around, stirred it around. And he said, "Now, get in there, take all your clothes off and get in that tub and take a wash rag and just soak yourself with that water, all over�your head and everything, face." In about five minutes I decided I would rather die! I was burnin' like hell, that old Lysol was eatin' me up! (laughter) Ooo! I was burnin'! Finally I got out, I dried myself off and the phone rang again�one of those old crankin' phones. It was the doctor. He said, "Did you get it all done? Did you get all that Lysol?" I said, "You son of a bitch! you wanna kill me?!" And he just died laughin'. He said, "You're burnin', aren't you?" I said, "You're goddamned right I'm a-burnin'!" And he said, "Well, maybe it'll kill those germs, I hope." But I never did catch it, so I guess it did. Ooo, man! I was scared. �.And you know they finally found that ruin was at least a thousand years

old. And those germs are still alive. They excavated that

damned thing, and boom! people all over the country had it. Isolated

the whole area�. They were building that ditch, and they cut right down

through the middle of it with their machines, building this irrigation

ditch across the San Juan River from Kirtland down to Shiprock.

They were gonna make a farm area for the Navajos out of Shiprock there.

They were building that ditch, and they'd been through that, and just

bing, bing, bing, they started gettin' spinal meningitis. The doctor

said that's what it was, and it's so contagious that they just closed

the whole works down�schools and all. That gal, how she caught it

or not, I don't know how she was over in that area. She must have

went up to Shiprock for something and got the bug and she died right quick,

and I buried her. But that Lysol must have killed those germs, 'cause

I put it all over me, just strong. ***

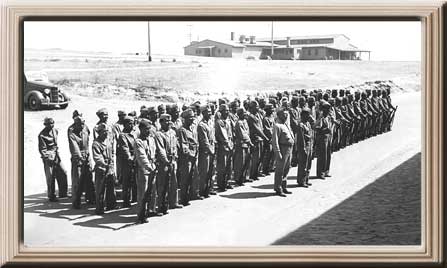

Jack Manning: I guess one of the things that I remember my dad telling about, was when they built the bridge across the river [in Shiprock]. They had the money for the bridge, but they had no money for the approaches. So now they got a bridge sitting across the river, and on one end it's twelve foot high. You'd have to climb up a twelve-foot wall to get onto the bridge. And so the superintendent there, they had a police force of two Navajo people, and the BIA superintendent, he told these two policemen, "You go out and you go up and down the river and you arrest every Navajo that's not working. If he's not working, you arrest him and bring him in here." And they did that, and they built the approach with wheelbarrows and

shovels. (chuckles) That would be interesting today!

If the guy wasn't hoeing his weeds, if he was leanin' on his hoe, they

just hauled him off. They had a compound there that they kept 'em

in, and they kind of slept on the ground. That was the way the approach

got built to the bridge�. *** Jewel McGee: Well�. They just had what we'd call the necessities. Their homes weren't modern, lived in hogans, and all that stuff. Of course their transportation was teams and wagons. I think when I first went out there, there was one Indian that had an

old pickup, and that was the car situation.

***

Peterson Zah: I was born in Keams Canyon area, on December 2, 1937�. My responsibility as a young boy was one of always helping out the family. My grandparents and my own parents would assign a task to me, and my duty was to make sure that those were carried out from day to day. For example, my parents were responsible for letting the sheep out in the morning. And then while that sheep corral was being opened, I was always having my breakfast. Once they got two, three miles up the canyon, then it was my job to follow the sheep. No questions asked, no argument�that was your duty. And the other thing was, that when you came home, there was always wood to be chopped, wood to be gathered. And that was also a duty I had to perform, because by that time my grandparents were getting up there in age�. You don't go to bed without any wood inside the hogan�. You always had to have that, because it gets cold�particularly in the wintertime. The animals had to go out and graze, and they had to be tended to from

day to day. So that was a duty that was ongoing all the time.

It was one of those things where you just had to learn how to be responsible

by doing, and very little talking about things. But you just worked

hard during the day, even as a young kid.

***

Stella McGee Tanner: Well, when we went out to Tsaya, Chunk bought a new Chevrolet, I guess

it was. But they didn't have heaters in 'em way back then.

And so whenever we would go to town, which would be about maybe once every

six months, and especially in the wintertime, we'd heat�we had these big

rocks, and we'd put 'em in the fire and just get 'em real hot and then

wrap 'em up and put 'em in the car, and that's how we stayed warm, with

our feet. And in the wintertime, it was cold, you know, driving

in. But they didn't have heaters in the car back there when we went

to Tsaya. ***

Leona & Jewel McGee: Leona: Of course when I first went out there, it looked kinda�here's these men been batchin' there, you know, and things weren't too (laughs) nice, but when I went in the bedroom, the bed had all four legs sitting in a tin can. And I believe it was kerosene inside. Jewel: Kerosene, yeah. Leona: Kerosene in the bottom of the can. And I said,

"Jewel, what in the world is that?!" Well, he said he did that to

keep the bugs from crawlin' into bed with him. And one night he

could feel something and kicked the covers off, and there was a great

big centipede crawlin' on his leg. And of course you know what that

did to me.

***

Peterson Zah: We had a spring where that spring was good to the family. It was always producing good drinking water. We kind of fenced it up so that the sheep and animals wouldn't go there. And it was preserved for family use. That�. was something that we utilized for many, many years. And I remember we used to have to take a bucket, a gallon- or two-gallon bucket, and going over there daily to get the water, both to my grandparents and to our camp. And that was a task that my father mainly did, because I guess he wanted to make sure that the water wasn't contaminated or anything like that. Sometimes on occasion I would take a gallon jug, and I would just follow him, and he would fill the gallon jug, and my job was to put it on my back and take it home. And my father always had two buckets with him. That was how we got our drinking water.

*** Marilene Bloomfield Blair: When I was about thirteen, Charles was workin' at the store, and he had a magazine called Ranch Romances. In the back of it, it had pen pals. So Paula and I decided we would write to, see if we could get our names printed in that magazine, and they printed mine. And I got letters from all over the world, and Raymond was one of them�. he was in the Marine Corps in the Philippines. And then he went to China. I have nearly all of his letters. Somewhere along in there, he decided he wanted me to quit writing to everybody else but him. So I did�. He wrote to Mother and Dad and asked if he could come to visit me. Daddy was very much against it. Dad had been in the service at Fort Windgate, and he said, "Servicemen are no good! Don't want you to have anything to do with this boy." So Mother wrote to him and told him that he was welcome to come. And then Raymond wrote to Mother and Dad both, and Dad finally wrote to him and told him he could come. And then when he got out of the service in Portsmouth, Virginia, I guess it was, instead of going home, like he should have, to see his parents, he caught a bus and came to Gallup and sent me a telegram when to meet him, and his telegram came with the mail, and it was late coming, so Grace and Charles and Ruthie and I crawled in the car and we went to Gallup to meet him. Grace and Charles and Ruthie run off and left me all by myself. And he had told me what he was going to wear, and I'd told him what I would be wearing, and we met on the streets in Gallup�. I was scared to death! About his first words to me were, "Do you want a strawberry ice cream?" I told him no. He said, "Well, how about a soda pop then?" I said, "No, thank you." Anyway, Grace and Charles and Ruthie finally came back, and we came to Toadlena, and there was some kind of a party there that night�. When we walked through the door, Dad met us at the door. Before that, when we started, it was kind of funny, Dad stood on the porch of the store and he shook his finger in my face and he said, "You'll be sorry, my girl; you'll be sorry! This is not the right thing to do!" But it was too late then. Dad looked Raymond in the eye, and Raymond looked Dad in the eye. They were just like that from then on. They were closer than Dad and his own sons�they really were. I don't know what it was, some kind of a charisma or something. (with emotion) They were buddies from then on. They hardly ever did anything without each other.

*** Mary May Bailey: One cold winter morning, the Collier's magazine had just come, and I was down at Mother and Daddy's and I'd been looking through it, and it was all about going to the moon, and how they were gonna get there. So I took it to Daddy and I said, "Daddy, look at this article. Do you think they'll ever get to the moon?" And he said, "Honey, I can't even begin to think about that. I've got to get to Holbrook this morning, and I can't figure out how I'm gonna do it!" (laughter) I thought that was a pretty good answer. Underhill: How did you see trading change over time? You saw it from the time you were very young. Bailey: Yes. It was a totally different thing--especially when they first started the CCCs [Civilian Conservation Corps], and they put those men to work killing.... What are they called? Prairie dogs! Prairie dog crews. So they would hire all of these young Indian men, and they would go out and use poison grain and hit every prairie dog town they could, to get rid of 'em. They thought they would bring an increase in the amount of grass. Well, that wasn't causing the overgrazing. The overgrazing was too much livestock. But that was one answer to the United States government. And at that time.... John Collier was his name, and he wanted to reduce all of the herds of the Navajos. So he forced them to sell--not taking into consideration that these were how inheritances.... Livestock was always an inheritance from the mother. She owned all the livestock. And if there were four or five children, they would just not have anything left if they had to kill all of these, which they did. And traders bought 'em and sent 'em to Kansas City by train. So his name just became a swear word among the Navajos. I don't know if you've ever heard that or not, but it was, it was just a swear word--they just hated him. Underhill: How did that affect your business? Bailey: Well, there was no price of anything at that time. You know, everything was Depression. But Daddy always managed to make money with his rugs and with the trading post--it always made a profit. Like I say, he was a shrewd trader and he knew how to do it. When they first started the draft--and that was before we were in the war--they sent all kinds of flyers out to all the trading posts to open up a place where these men could come and register to sign up for the draft. So Daddy thought that was a real good idea, so he put a.... We had a big ceremonial hogan that he had bought after one of the ceremonies close to Castle Butte. He bought the whole thing and had the men come up and set it up by Castle Butte, because it made a wonderful place to have an extra bedroom or just extra room, which we didn't have much of. So he put up a flag pole and flew a flag, and put a big Navajo rug out there on the side of the hogan, and that's where these men signed up. Well, that morning that they were to sign, this young Navajo man came. One of the first ones, and he had a bedroll on the back, and a rifle mounted in a scabbard on the side of his saddle, and he hung around all day long after he signed up. He was still there when we were eating supper. And Mom said, "You know, I think you ought to go out and ask that man what he's waiting for, Jot." So Jot puttered out, he asked him what he was waitin' for. He said, "I'm waiting to go to war. I'm all ready. Just as soon as they tell me where I can go, I'll go." And he said, "Well, it doesn't work that way. You've got to wait 'til you're drafted." But they were good people. My, a lot of them were very good--real good friends. When Daddy died, they came to Mother immediately, two different medicine

men came. And they said, "We want you to know that we're having

the same ceremonies for Jot as we would have for our own." ***

Peterson Zah: Early on, my father went into the service, maybe around 1937, 1938, 1939. He was training and preparing to become one of the Navajo Nation code talkers when the war was over. When he came back, he came back to the family as an alcoholic. He liked his booze, and we could never get him away from that. But he didn't drink all the time. He was one of these, I guess, individuals that drank very heavily for a short period of time, and then left it alone for the next couple of months or so. He had a great sense of responsibility towards his people. For example, he would go to the trading posts and he would get mail, an envelope like this, because he knew all of these people whose name was on there. Mary Yazzie. He would look at it and say, "Mary Yazzie is our neighbor, seven miles up the road." So he would get all of that, and then he would ride his horse to Mary Yazzie's house, and then he would deliver the mail to Mary Yazzie. Well, Mary Yazzie can't read or write, so then he would give it to Mary, and then Mary Yazzie would open [it]. He always had them open the letter, and then they gave him the letter and he would read it to them in Navajo. And he would interpret from English right into Navajo words. And nine times out of ten, those Navajo ladies would say, "We want you to write back to this person for us." And so my dad would sit there and the ladies would tell him what to say. And so he would write back to the people. Most of these letters that I remember as a young boy were letters that came from young men that were in the service during the war. And I remember him reading to his own brothers and sisters what kind of war was going on, what happened at night, and the Japanese, what they looked like, and how they were so lucky, and all of that. And the letters would say something like, "I don't know if I'll return home, but I'm just telling you the way life is here when you're in the service." They would describe the food that they would eat, and the long walks that they had to take, and how they got thirsty, let's say, on one trip, and one of their buddies would get killed. That� kind of some horrible war stories that they would write about. And I remember some elderly Navajo women would cry as my father would read the letters to them. And then my dad would say, "Let's go to another camp to deliver another letter." So I would sit on the back of the horse. We had one horse, so I would just sit in back of him, and then he would deliver the mail to the next person. The same thing would happen. And I remember a lot of times when the people who are in the war, they

will not put their address down, and the ladies want to write back, but

there's nobody to write back, so they know that the letter came from their

son. So my dad would just say, "We'll wait for the next letter.

Maybe they'll have a return address. That way I can write back to

them for you." *** Marilene Bloomfield Blair: Raymond went [to the Marine Corps base in San Diego] when they drafted him. They put him on the rifle range, because they couldn't get through to the Navajos what they wanted them to do. And Raymond said he made sharp shooters out of every one of them. So they thought the Navajos were pretty good at that, after Raymond could talk Navajo to them and told them what he wanted done, and teach them how to shoot, 'cause Raymond was a sharp shooter in the Marine Corps, too. He's got medals for that all over the place. I don't know where they're at�.

***

Sally Wagner: We had a radio. As a matter of fact, the one and only time I have ever listened to short wave was a Sunday morning--I hate gadgets--I hate that thing over there, that TV--I just don't fiddle with them--but that one morning, for some reason, I was fiddling with the short wave, and I got the bombing of Pearl Harbor. (long pause) Underhill: What impact did World War II have on your area? Wagner: Oh, tremendous impact, because the men either all went into war industry or went into the service. And then, of course, when they came back, they'd seen the outside world, and they had ideas. That's when we realized that the Navajos were going to change. We didn't want to see it happen. Underhill: What kinds of ideas did they come back with, after they had seen the outside world? Wagner: Well, let's see, they wanted more possessions than they'd had before. They weren't as sure about their own culture as they had been before. And of course that marginal state is very destructive to the individual.

Grace Bloomfield Herring: We did a lot of work with the people in the Army. Charles wanted

to enlist, they wouldn't let him. He said, "You're doing more here

with the Navajo people to help them than if we would put you in the Army."

He says, "You stay right here." So he did. I can remember

we did all kinds of projects. I can remember one time that all of

the Indian women wanted to learn to knit for the Army, and golly, we made

sweaters and socks and everything. I can remember my front room

and bedroom and other bedroom being full of Indian people learning to

knit�.. They'd come in with those things quicker than I could even think

of doin' 'em. They really worked hard�good people. And Charles

and Mother both spent a lot of time writing between families and the boys

that were in the Army. They kept the correspondence up with them,

which was a good thing to be doing. Charles did that, too.

In fact, just recently we sent some things to the Nez�s family that they

had given to Charles�some money that this boy had got over when he was

in Japan and Korea. I sent and gave that to them just recently,

that they had given to Charles.

***

Jack Manning: I worked in [Bernard�s] as a kid, oh, from 1942, 1943, 1944. Everybody was drafted and in the war, and there wasn't any help. I stocked shelves and counted ration stamps and all those kind of things�. You had to have your coupons to get sugar, and so many for canned goods. As far as the way the rationing worked, it was there, same as it would have been in New York City, I guess�.It was just distributed there, and they had an office there in Shiprock and they would go there and get 'em. Back at that time, their diet was pretty much mutton, fry bread, and coffee. Your trading post didn't have the fifteen different varieties of the same item, you know. They had one kind of tomatoes and one kind of peaches and one kind of flour, and that was about it�. Shiprock was very small. The safest place in the world. Probably not any more place in the world safer than Shiprock as I grew up. I can remember my folks would let us�down by the BIA high school they had a lot of concrete sidewalks and lawns, and it was nice. We'd go down there rollerskating ten, eleven o'clock at night, and be perfectly safe. There was probably, let's see, maybe ten or twelve BIA homes. And other than the trading posts, there was Shiprock Trade, and Bernard's, and Bond and Bond. That was the extent of the businesses. And one garage�there was one garage, one place to buy gas.

***

Tobe Turpen: I joined the Navy. My father was in the Navy and he wanted me to join the Navy, which I did. I ended up bein' a gunner off of a torpedo bomber on aircraft carriers…in the Pacific, uh-huh. You asked me if there was anything I didn't want to do over--I wouldn't want to do that over. I just barely got home from that… We were in that big Philippine Sea battle, and we lost a lot of planes and a lot of ships. As you look back, it was a great experience, but you wouldn't ask for it again. You know, just to show you how important money was, I volunteered for that. I went to gunnery school. They put me in gunnery school, didn't give me much choice. You go through gunnery school and you learn about the guns and so forth. And then one day they had a bulletin board there, and they said, "We need volunteers for, air crewmen," they called 'em. And they said, "You'll get flight pay." That's double your pay. "Plus if you go overseas, you'll get extra hazard pay." So now you're gettin' almost 300 percent. You're gettin' 200 percent more than you wouldda made. And that's why I volunteered--for the money. (laughter)

***

Mary May Bailey:

Bailey: Well, it was huge. They had to keep the cards and vanilla in the safe--which was a strange thing for me to think about.... And we played in the wareroom and jumped in the wool sacks, and we had a great time. And that's where Roger found the dinosaur print. And there's lots of pictures of him with his feet, to give an idea of how big those prints were. And then Daddy always told us that over in that same area there were hoofprints of miniature horses. So somewhere over there in that area, they must still be there. And I can remember when we came to Flagstaff, you could see dinosaur eggs everywhere. Some were very large, and some were quite small. And you couldn't find one now if your life depended on it. And I've often thought, "Why would somebody take those?!" I don't know what they could do with them--maybe cut 'em in two to see if there was an embryo in. But it's always amazed me. Let's see.... We had a one-room school, grades one through eight. The Curley [phonetic spelling] kids went to school with us, and the Richardsons, and then that was Bill and Harriet. And then the other Richardsons lived at Cameron, so whenever we went to Flagstaff, we'd always stop by and saw them, and they had three children, and they all died very young. I don't know what happened there. Over at Cow Springs there was another little girl I used to play with occasionally. And then there was some on up the way. About this time they were getting ready for putting the bridge across Lee's Ferry. Now, we went up there, and I don't know what for. I rather imagine it had something to do with sheep. But I can remember going down the dugway and I have pictures of Betty and Roger and I sitting on the bank, waiting for Daddy to help the man get off the sandbar. And we went and stayed in Kanab, and it rained and rained and rained, and we couldn't get back for a week, so we had to stay in Kanab that time. Then on our way back.... Let's see, what was that girl's name, that lived at Lee's Ferry? Anyway, she was a real nice girl, and I enjoyed her. So when they opened up the bridge, Mother and Daddy and I guess everybody else that could make it, went to the dedication.... Now, I have pictures of when they started, and all the way across. But while we were there, they just kept playing, "When It's Moonlight on the River Colorado," and Mother and Daddy danced and danced all night long. Then the next morning we went to the dedication and some guy in an airplane just like that one went underneath that bridge and out. Oh, I just can't imagine anybody having that kind of nerve. But that's when we went across there, and I guess they built another one, now, because that wouldn't handle the trucks.

Underhill: What movies were filmed at Tuba? Bailey: Sunset Pass was the last one. But there were others that came and went. Then one night everybody had gone to bed, but Daddy had left the light on. And somebody banged and banged and banged on the front door, and he went to the door finally, and there were two men standing there, and they said, "Is there any way we could get anything to eat? We've been lost out here since early morning." And it was Gary Cooper and the man that was with him, and they came and Mother got up and fixed them breakfast. Then they stayed the night, and then they went on the next day. His signature is in that book. We met lots of people. Will Rogers came through on his way to the snake dancers, and at that time lots of people could go to the snake dances. It was just really an occasion. So we always all went. Or other dances. The home dance is just as beautiful as anything of the others. The snake dance scared a lot of people, because the priests would let those snakes run clear back to the people, and then they'd pick 'em up--they wouldn't have a chance of getting bitten, but they didn't know that, and it scared the puddin' out of 'em. (chuckles) And you could see 'em just drape 'em over, and drape 'em over, and drape 'em over, and then they'd wrap around there and bite sometimes that way. But it was very interesting. Underhill: Can you describe the store for us? Bailey: The store was a big hexagon, and all the way around was--they had a big opening where the big double doors opened and came in, and that was always called the bullpen, and there was a big stove in the middle, to get warm in the wintertime. And they all managed to, there was always a coffee pot going. And on the counters there was always a cigar box with a spoon tied with a string, and made permanent with that box. The box was filled with tobacco, and there was always papers. And there was always an odor about a Navajo trading post that if I was to go in one today, I would recognize it immediately. There was a mixture of wool, ground coffee, and all of these other wonderful smells--oh my!--and hides. Some smells not so good, and some smells good. It made it just wonderful. And cheese! They always had a big block of cheese that they could cut cheese off. And then all mainly canned goods. Lots of pawn. Lots of big, heavy safes. I don't ever remember being robbed at Tuba, but we were robbed one time at Castle Butte, and I'll tell you that story later. Anyway, when it got to be close to the thirties, my father knew it was time to get out. So he sold his interest back to the Babbitts and we moved to Winslow. He didn't know exactly what he was going to do, but he thought he wanted to go into the cattle business again. So he found a ranch out of Holbrook that was thirty-five miles north of Holbrook, that was the Turkey Track Ranch, and he bought it and stocked it. And we moved to Turkey Track. Well, by this time, my sister is in the eighth grade, and Mother knows that she cannot.... For a while, we moved to town and Daddy stayed at the ranch, and then when Betty got to be an eighth-grader, the Depression was pretty bad then, so they boarded her in town, and Mother taught Roger and I at home. So we had a marvelous time. We could do our studies in the morning and go play all day. Once in a while Mother would ride with Daddy, but he said it got too expensive, he couldn't afford all that Absorbine Jr. [Tr.'s note: liniment for aches and pains]. (laughter) And I can remember one morning Mother saying, "Well, am I going with you today?" And he said, "No, not today. This would be two bottles of Absorbine Jr." (laughs) So it was rough riding. But Roger learned to ride really well. I guess Daddy started from the first, and then I was part of the learning process. He would yell at me, "Mary May, run by me and beller like a bull!" And he'd rope me. (laughter) So I had a lot of rope burns early on. But it was fun, we just had a great time. He was one of my best friends. And he was killed in World War II, Achen, Germany. He was in the second wave that came into Normandy, and they fought all the way across to the German border. He was a staff sergeant. Anyway, that nearly killed my folks, when they lost him, but we went on.

***

Paul Merrill:

And of course in Ramah, New Mexico, then, there was no running water, there was no heat, and no electricity, and I had to heat water on the stove, and took a bath in a number three tub and put on my best hand-me-down clothes and went downtown and luckily I caught a ride to Gallup that same afternoon, and by five o'clock that afternoon, I was officially signed up to the Marine Corps. We had to go to Denver, Colorado, to take physicals and finish everything out. We were in the back of a pickup-five of us-and we got to Santa Fe that same night, late. When I left home, I only had fifty cents in my pocket. Of course fifty cents in those days was a lot different than it is today, because a nickel would buy a Coke, and a nickel would buy a hot dog. And so that wasn't too bad. But we got to Santa Fe and the Marine sergeant had forgotten his chit book. It was the month of July, fairly warm, so he said, "Well, fellahs, we're gonna hafta sleep in the park tonight." That was all right with us, so we all bedded down in the park, and pretty soon the police came by and said, "You can't do that." And he told 'em the circumstances, and the policeman said, "Well, I have an idea. We'll let you sleep in the police station, and they'll give you breakfast in the morning, and this certainly won't go onto your records." And that's what we did, we went and slept in the jail that night and they fed us breakfast the next morning and sent us on our way to Denver. We took our physicals in Denver and then shipped to San Diego, California. Within the next year, I was at Pearl Harbor. I stayed there until the Japanese came. I was at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese bombed, and they extended my tour of duty four-and-a-half years. I'd have been paid off in about six months when they came along. So during the war I went to officers' school and spent about five years out in the Pacific. I came back to the States and went to officers' school and then spent some more time in the Pacific, and came back to the United States and trained men and were boarding a ship to go for the landing on Japan, when they declared the war over. President Truman had dropped his two bombs, then the war was over by then. So we de-boarded the ship and unloaded our men.

***

Mary May Bailey: I think it was June 4, 1942 or 1943. I was staying down at Mother and Daddy's house, and I must have been sleeping on my right side, facing east in the bedroom on the east side of the house. My father was sleeping in another room, but he must have been on his right side, too, facing the east. It must have been between four and five o'clock in the morning. We both woke up and jumped out of bed and said, "What in the world was that?!" And there was no noise, there was just this horrible bright light. So Daddy wrote it down in his little ledger that he kept about everything that happened every day. When the war was all over, they finally told us that they'd set off an atomic bomb down in New Mexico, and that's what it was. You could see it from here, if you were upstairs. So my, what a mammoth thing that must have been. Now, that's a long distance. But it must be on that strata.

***

Edith Nichols Kennedy: I was taking flying lessons, and Troy started taking flying lessons. We started dating then. Finally we were going steady, and then World War II started, and he was one of the first ones drafted into the war. He went into the Naval Air Corps. After he got out of boot camp, he was sent to Kingsville, Texas. I went down there and roped him in-we married (laughter) in 1942. And then when the war was over, we came back to Farmington, and that's all he knew, was the trading post business, because he had worked for his dad [William Leroy Kennedy]. And Troy had worked at Lukachukai Trading Posthis dad and brother owned that. He had worked there and spoke Navajo fluently�. As soon as he came back, there was a huge piñon crop over on the Lukachukai Mountains. Just every five, six, seven years, there's a piñon crop. That year there was a piñon crop, and his brother, Earl, at Lukachukai, needed help. We went straight from being released from the Navy in October to Lukachukai and helped him with the piñons. I had never been on a reservation in my life, and it was all new to me�. We were glad to be at Lukachukai. We were snowbound that Christmas, and we couldn't get out. So we just had our Christmas with the Navajos at the school, and the Catholic priest was there at church, and we joined right in with them and had Christmas along with them. I would go in the trading post and work, trying to learn a little of the trading business�. [Then] for two years we worked at the Fruitland Trading Post, owned by

Jack Cline. He hired us to work for him across the river at a little

store called Southside Trading Post. And it was Nenahnezad area.

We worked there two years. And then Jewel McGee needed someone to

work for him at the Red Rock Trading Post at Red Rock, Arizona.

It was called Red Rock, Arizona, at that time. It's now Red Valley.

We bought an interest in Red Rock and moved out there in 1948.

*** Jack & Evelyn Lee: Jack: In the late thirties I was on the railroad. I worked out of Gallup on the railroad, and then I transferred to Third District in Winslow, from the First District. And then I went into the service... when I got out of the service, I was an engineer. I went in as a fireman�. So I hurried up and took the engineer examination and became an engineer, and I only had maybe a year experience as a fireman! (chuckles) And I became an engineer in a hurry. And then we worked like the dickens after the war was over, gettin' our people all back to where they come from on these troop trains. And then everything died and we was out of a job. Evelyn: When he married me, I told him I wasn't livin' in Winslow�. back to the reservation. Jack: So I said, "Well, the only thing I know anything about

is workin' on the reservation." So I went to Ganado, and my nephew

was runnin' Ganado�Hugh�and he hired me out there. He was my tutor

for GI schooling, and I got salary plus schooling, and I taught him how

to trade. He didn't know nothin' about trading, but he was my boss,

he was my teacher. We got an extra $105 a month for goin' to school.

Cole: I was going to ask you, [Evelyn], what it was like for somebody that had grown up in Arkansas, when you first went to Keams Canyon, what was your reaction? Evelyn: You know what, I couldn't afford a reaction. We were tryin' to make a living. We had three boys. He has two sons, and then Snick. We had to pioneer our store. Jack: It was from nothin' to nothing. Evelyn: In the first year there, at the end of the year, after living out of the store, our part of it was $98. Jack: For a year. But we did have a house on our head and somethin' to eat. Evelyn: Yeah, we had two rooms.

*** Elijah Blair:

I was in the service in the forties, and I was discharged actually the end of '47�I think I came out January 2, '48, and I was goin' back to school. Actually, I went in at the end of the war, but they were still drafting, and so I went in and actually went into the Army for about eighteen months, two years, and I was goin' back, usin' the GI Bill to go to school, 'cause I didn't have any way to go to school, and I had actually applied to go to school at Ohio State. Just before I was discharged, my brother sent me a one-way ticket to Cortez, Colorado. I was discharged in Denver, at Fitzsimmons Hospital where I was stationed. Raymond owned a store at Mancos Creek, just south of Cortez, and I came in January, I think, of '48. And then I stayed there about two weeks, and I always teased my sister-in-law that she got tired of feedin' me, so she got me a job at Toadlena Tradin' Post, which was actually her sister and brother-in-law�s� Here I am. |