An Ancestral Landscape

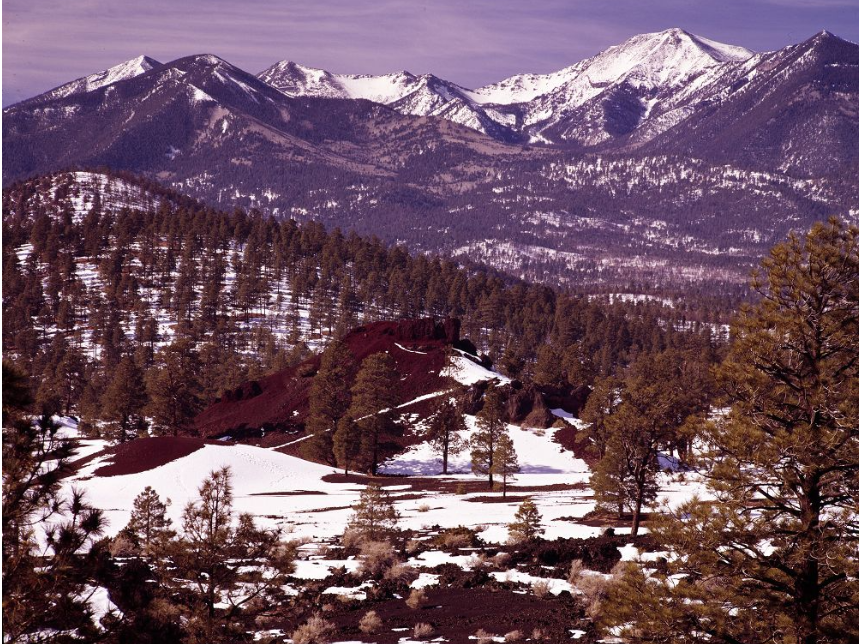

Northern Arizona University sits at the base of the San Francisco Peaks, on homelands sacred to Native Americans throughout the region. We honor their past, present, and future generations, who have lived here for millennia and will forever call this place home.

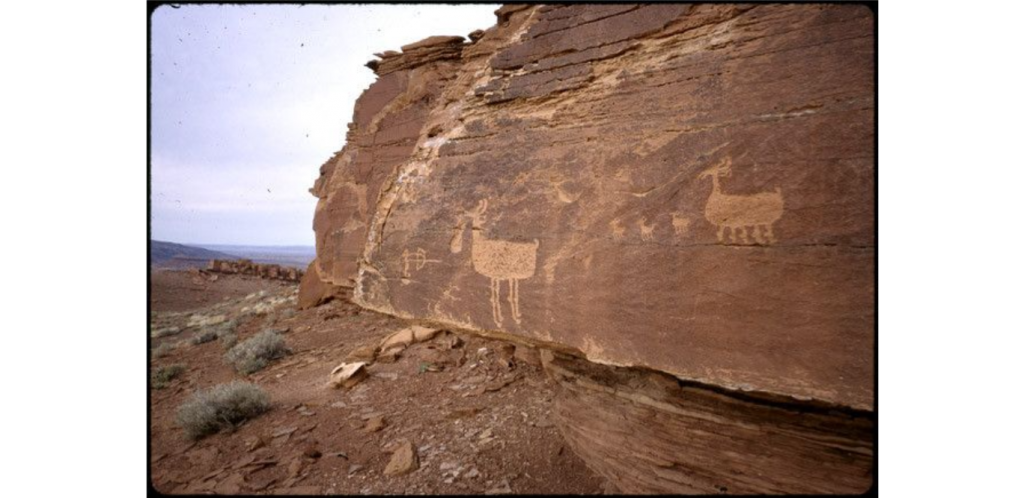

Northern Arizona’s logging legacy predates the arrival of European settlers. At least thirteen federally recognized tribes have lived throughout today’s northern Arizona and the Four Corners region for millennia, including the Havasupai, Hopi, Hualapai, Kaibab Paiute, Navajo, San Carlos Apache, San Juan Southern Paiute, Tonto Apache, White Mountain Apache, Yavapai, Yavapai-Apache, Yavapai-Prescott, and Zuni. Through this long-term stewardship of the environment, Indigenous ancestors have passed down a vast understanding and knowledge of self-subsistence and resource care from generation to generation—a tradition that continues today.

Indigenous groups have lived in and cultivated what is today referred to as North America for thousands of years. Thom Alcoze, Diné (Navajo) ecologist and former associate of the NAU School of Forestry, noted that people have cared for all of North America’s unique ecosystems throughout time. “There were no vacant habitats at the time of Columbus’ arrival or at the time of settlement,” said Alcoze. “People were living there, and they were organized with language and government and territory.”

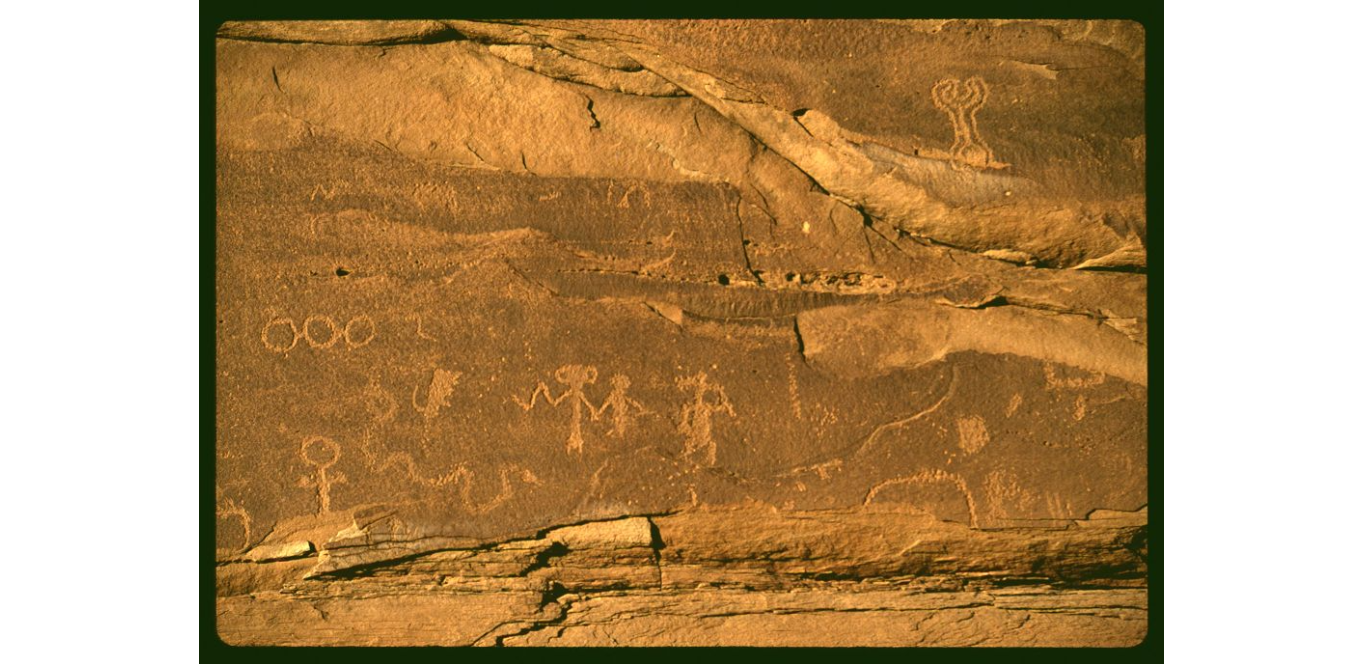

Indigenous cultural traditions inform environmental care practices. In Hopi tradition, every natural being from the mountains to the trees is a living being with a unique life and spirit. The actions of all spiritual beings are related and are, therefore, obligated to act in consideration of one another to uphold a harmonious life. Diné ecological tradition upholds that when an individual uses a resource from the environment, they are obligated to ask permission from the earth, give thanks through a ceremony, and give back to the environment in some way. Both traditions maintain that respect is at the core of environmental care. These traditions have remained integral to the region’s Indigenous communities. Today, northern Arizona and its various Indigenous cultural heritage sites are significant places of ceremony for the region’s local tribes.

In Indigenous environmental care practices, the use of the land is a responsibility and is an act of reciprocity. Prescribed burning is an example of giving, a practice that has been utilized by Indigenous communities to promote rich and fertile soil for crops and forest health. According to the former director of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office and Hopi Hotshots wildland fire crew member, Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, prescribed burns help reduce the buildup of ground fuels, leaving a layer of ash that allows plants more nutrients and exposure to sunlight. This fire management practice emerged from a careful long-term observation of the environment and a deep understanding of its patterns, which has become integral to modern fire management practices.

In the more recent battle against high-intensity wildland fires, the U.S. Forest Service has turned to Indigenous communities for guidance on fire management which established an education discourse known as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). The National Park Service defines TEK as, “the ongoing accumulation of knowledge, practice and belief about relationships between living beings in a specific ecosystem that is acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment, handed down through generations.” Today, the U.S. Forest Service and wildland fire crews throughout the United States utilize prescribed burns to promote the natural ecological patterns of the environment and to minimize the ecological damages caused by future wildfires.

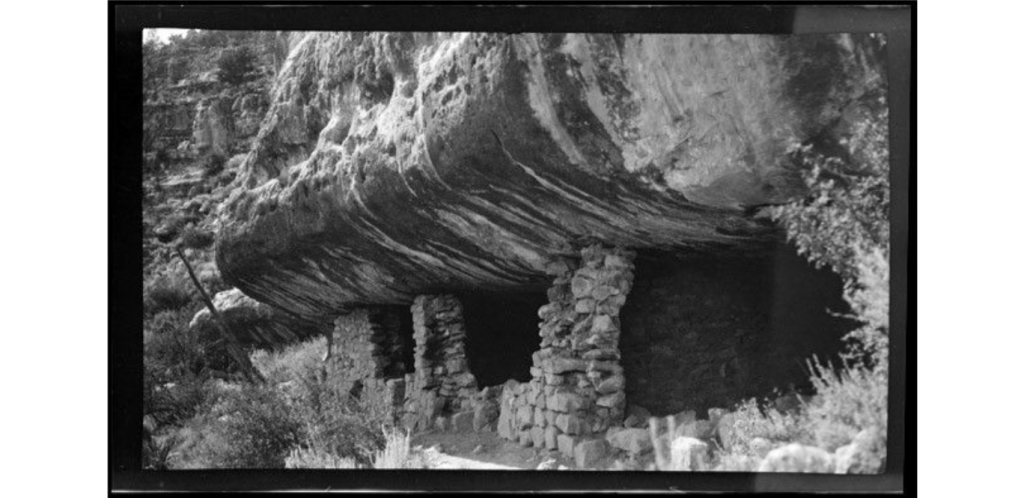

Northern Arizona’s Indigenous communities have historically harvested timber for fire fuel and construction materials. From the wooden support beams used in the Ancestral Puebloan sites of Wupatki, the cliff dwellings of Walnut Canyon, and Elden Pueblo, to contemporary maintenance and care of home and communal structures in Hopi villages, lumber has sustained northern Arizona’s Indigenous communities for countless generations and continues to do so today.

When moving through the exhibit, know that northern Arizona’s Indigenous people have never left this region and continue to be a part of northern Arizona’s logging legacy. Whether they work in the woods logging for any of the local lumber operations, aid the scientific research effort for the U.S. Forest Service, serve on wildland fire crews, teach forestry in academic settings, or demonstrate environmental care in any way, Indigenous peoples remain important actors in the story of forestry in northern Arizona. Their unique histories and traditions are deeply integrated into the continuing timeline of northern Arizona’s forest science history.

——

[Cliff Dwelling at Walnut Canyon, Arizona. 1920-1940. Emery Clifford Kolb. NAU.PH.568.2295.]