1890: The U.S. Forest Service

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Americans grappled with the understanding that the nation’s timber resources were not limitless. Timberlands throughout the east coast, the southeast, and around the Great Lakes grew increasingly thin as large timber companies logged forests for commercial use. Contemporary practices threatened the long-term availability of natural resources in the United States. Working toward a solution, Congress enacted the National Forest Preservation Act in 1891, allowing the President to designate certain forests for protection and management. This marked the beginning of the Forestry Bureau, which would later be renamed the United States Forest Service.

President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) established Arizona’s first forest reserve in 1893—the Grand Canyon Forest Reserve—which included the canyon itself as well as the forests along the north and south rims of the canyon. In 1898, President William McKinley (1843-1901) designated the San Francisco Mountain Reserve, which included today’s Coconino, Kaibab, Sitgreaves, Prescott, Apache, and Tonto National Forests.

Flagstaff’s first Forest Service crew came to the area in 1897, led by their supervisor Fred S. Breen. Regional leaders of the Forest Service at the time were generally not trained foresters. Rather, they were well-versed in political processes and skillful in communication, which was important for the new agency to gain public support and acceptance.

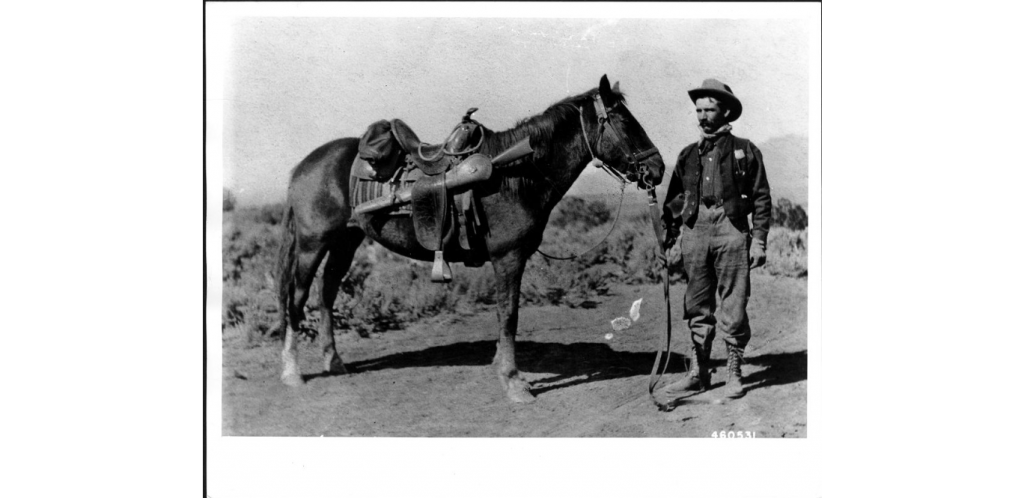

In its early days, the Forest Service employed men from various backgrounds. According to Willard M. Drake, a former forester of Arizona’s Black Mesa Forest Reserve (now Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest), Forest Service crews were often made up of a mixture of “cowboys, prospectors, barkeepers, professional gamblers, farmers, lumbermen, sheepherders, gunmen, ex-soldiers, and whatnot leavened with a sprinkling of university graduates, clerks, clergymen, newspapermen, carpenters, and ‘lungers,’” many of whom he would not consider qualified for the job.

As the United States government regulated timber usage to conserve the nation’s natural resources during the turn of the century, settlers and large timber companies in northern Arizona faced legal complications that hindered subsistence, intensive logging operations, and lumber production.

Timber usage regulations under the Forest Preservation Act “locked up” the forests by imposing heavily restrictive limitations on how much timber could be used, spurring controversy among Arizona settlers and timber companies. Settlers in Arizona and large timber companies were required to obtain timber-cutting permits that involved extensive paperwork and correspondence with the United States Department of the Interior, even for as few as five cords of wood.

NAU.PH.136.

On tree marking operations, foresters typically “cruised” the woods, scanning for trees that fit a certain criteria to be selected for logging. They considered the age, maturity, and condition of the timber, then marked trees of 11 inches in diameter. However, diameter criteria were waived if foresters found it necessary to “thin” the forest or clear out a certain number of trees from an area to encourage the growth of surrounding trees.

Early Forest Service Rangers were responsible for marking trees that timber companies were permitted to cut and process into lumber. This process came as a difficult adjustment for the AL&T Company, which previously operated on a “clear-cut” basis.

NAU.PH.138

In 1905, the Chief of the United States Forestry Division, Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946), transferred forest management from the General Land Office to the Department of Agriculture, bringing about a shift in conservation procedures. Pinchot emphasized the renewable aspect of timber as a natural resource and pushed for systems of planned use instead of total preservation. To this end, the Forest Service also sought to cooperate with the nation’s timber industry instead of pushing against it as the previous conservation policies did.

With American forests now under the jurisdiction of the Forestry Bureau—a transfer instituted by Pinchot with the support of President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919)—Arizona timber companies were allowed more generous land rights after 14 years of highly restrictive timber-use regulations. Forest Reserves were then renamed National Forests under the Forestry Bureau.