1887: The Arizona Lumber & Timber Company

The Arizona Lumber & Timber Company’s convenient location within the world’s largest contiguous ponderosa pine forest proved to be profitable for the company. The AL&T Company supplied the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railway with railroad ties from Flagstaff westward until the line reached the Colorado River.

——

[Laying Track at the Arizona Lumber & Timber Company. AHS.0020.00193.]

The AL&T Company remained Flagstaff’s largest employer for roughly 50 years. Railroads were the greatest source of profit for the lumbering industry, which encouraged D.M. Riordan to seek a market for railroad ties beyond Flagstaff along other developing railroad lines. The Riordan brothers invested in lines surrounding Los Angeles, Barstow, Needles, Albuquerque, and Globe. The AL&T Company also supplied timber for bridges, telegraph poles, mining structures, fruit and vegetable boxes, and individual homes during its heyday.

By 1890, the AL&T Company owned all timberlands in the San Francisco mountains amounting to 871,040 acres and one billion board feet of timber. M.J. Riordan, who served as the company’s secretary at the time, boasted, “The company has an absolute monopoly of the most compact pine timber property between the two oceans… The last of our competitors have been removed.”

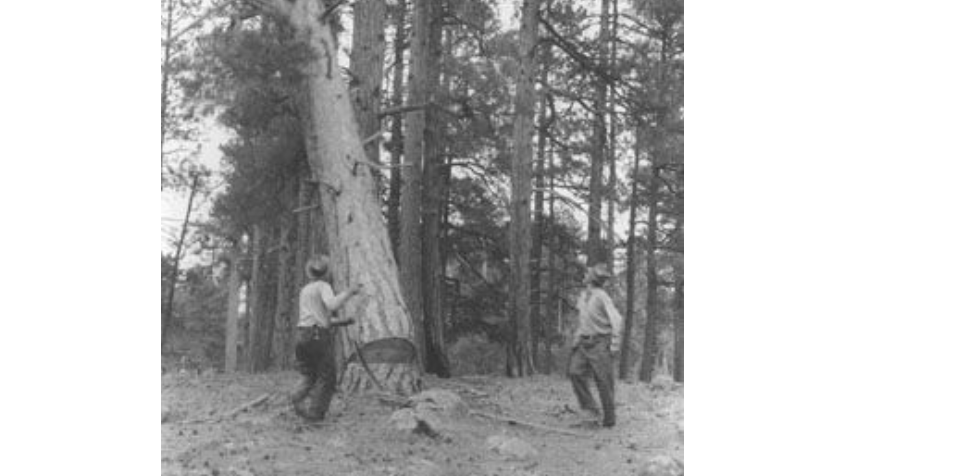

Logging Arizona’s ponderosa pine forest required an all-hands-on-deck approach. Teams of AL&T Company lumberjacks worked in the woods near Flagstaff to fell standing trees using axes and crosscut saws. Before the introduction of federal timber regulations—a time when lumbermen understood little about the ecology of forests—companies such as the AL&T Company operated on a “clear-cut” basis, cutting down as many trees as possible within their land grant to turn the greatest profit from their resources.

An axeman guided a tree’s falling direction by the shape of the undercut he made on the side of the tree’s trunk. This step required much skill and precision to ensure that the tree would not damage surrounding trees or injure nearby lumberjacks as it fell, and to conserve the maximal amount of timber from the tree.

After felling a tree, lumberjacks “swamped” it by stripping the trunk of its protruding branches and bark knots. Loggers with crosscut saws, called “sawyers,” then “bucked” the tree down to at least thirty feet in length using crosscut saws. This process allowed lumberjacks to more easily transport fresh timber from the woods to the nearest AL&T Company sawmill.

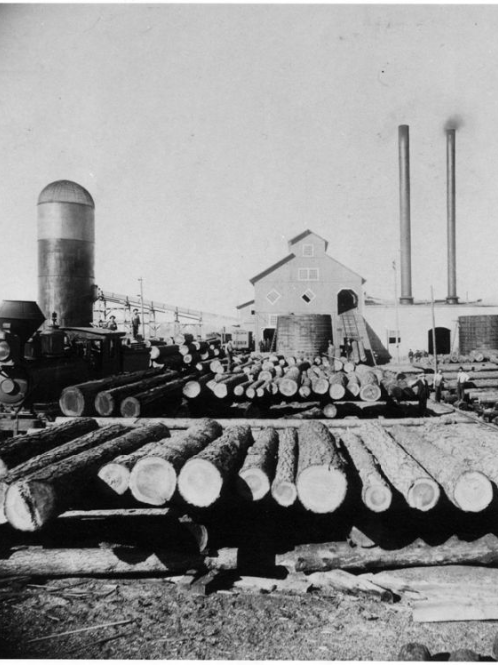

AL&T Company woodsmen then loaded timber onto logging wheels using hooks and chains. Oxen, mules, and horses typically pulled the loaded timber on these logging wheels to the nearest wagon or railroad spur where they would be delivered to the nearest sawmill.

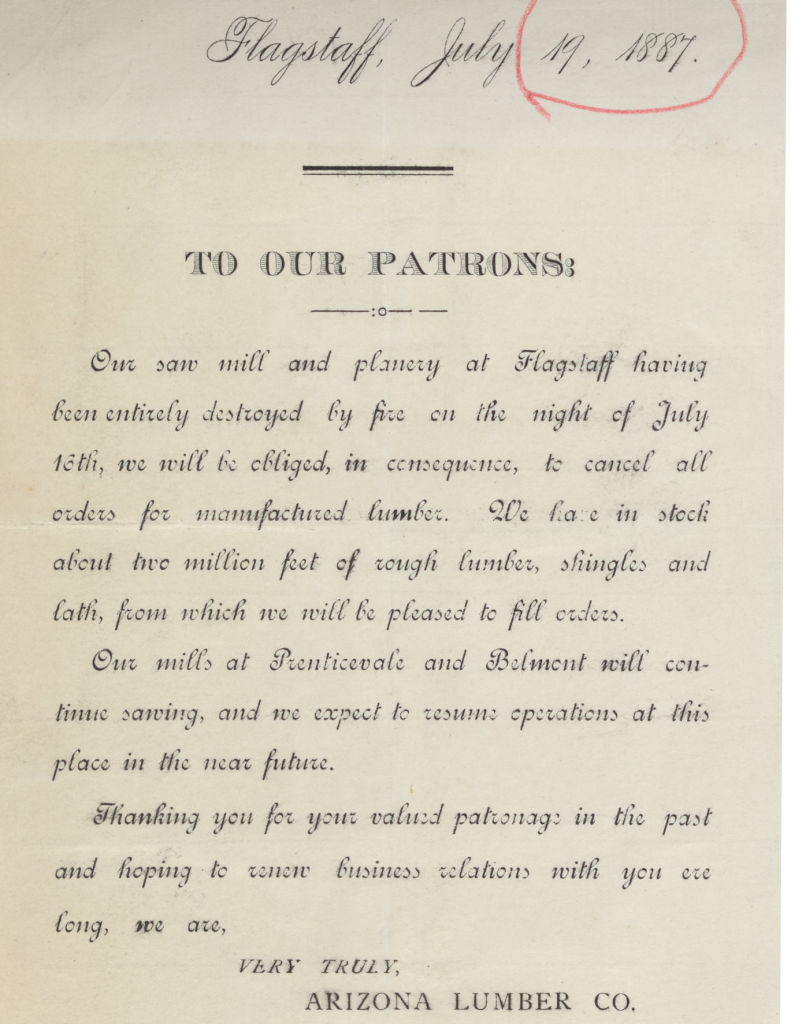

The Arizona Lumber & Timber Company continued to struggle with fires. While on a business trip to meet prospective investors in Chicago, AL&T Company president D.M. Riordan received a startling message from his brother, Timothy A. Riordan, who was in Flagstaff overseeing the sawmill. A fire had started inside the sawmill after dark on July 16, 1887, which destroyed the entire sawmill and a portion of the lumberyard.

D.M. Riordan immediately gathered funds to replace the Flagstaff sawmill with two new sawmills and ordered the machinery to be shipped to Flagstaff. For D.M. Riordan, having an additional sawmill in Flagstaff protected logging operations in the event that one burned down again. After making these arrangements, D.M. Riordan triumphantly announced in a telegram to an editor of the Arizona Champion on July 21, 1887, “Takes more than fire to down me permanently.”

——

[A letter addressed to AL&T Co. patrons announcing the July 16 sawmill fire. Riordan Scrapbooks volume 1, page 49.]