1950: The Automobile Industry

Automobile manufacturers around the world took advantage of the abundance of steel available following the Second World War to create new, stylish vehicles. Automobiles gained renewed popularity in the United States as they were marketed as symbols of individuality, freedom, and luxury to the public.

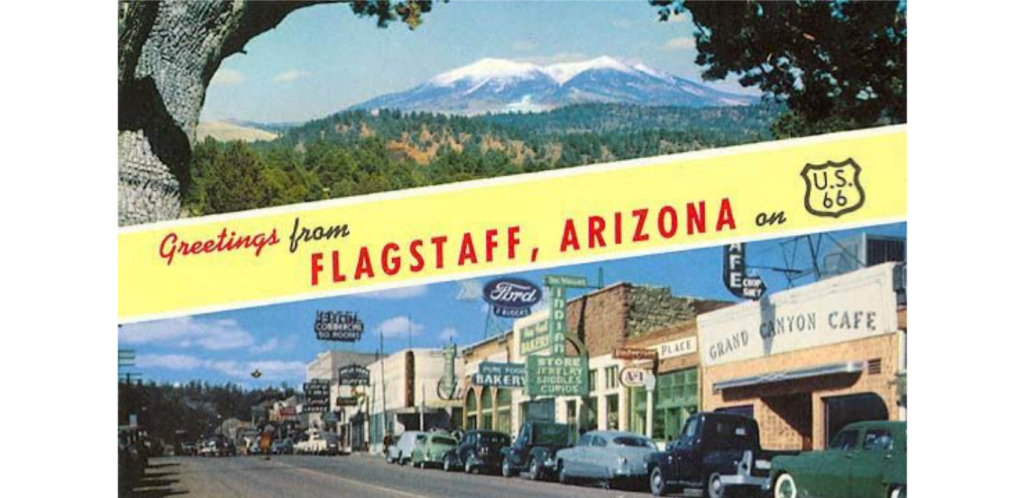

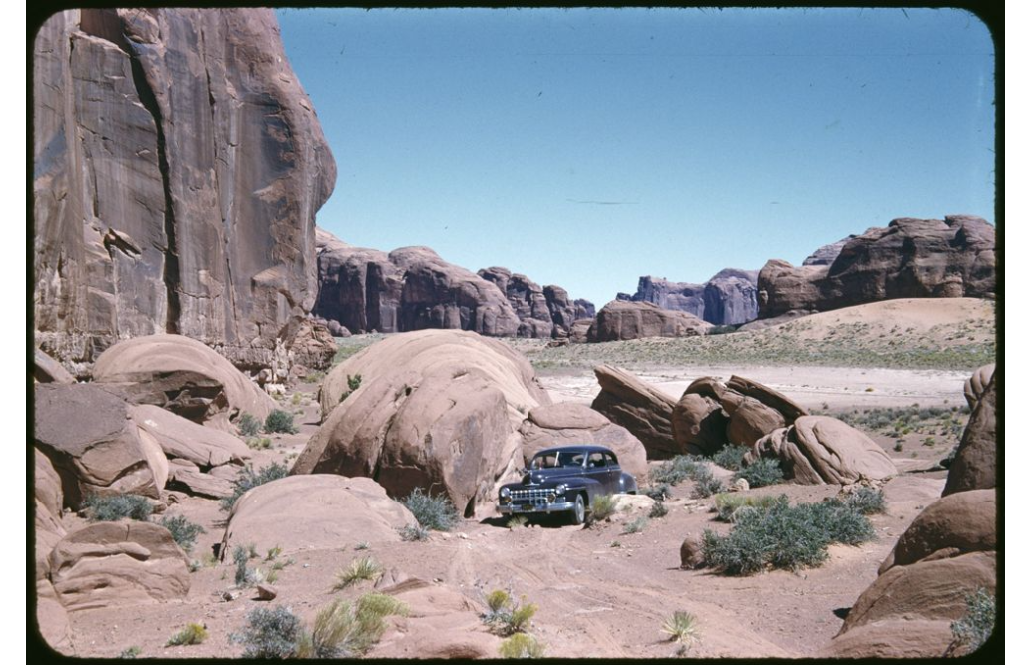

The rise of the automobile industry combined with the popularization of interstate highways such as Route 66 allowed automobile tourism to take off. Tourism quickly became Flagstaff’s second largest industry alongside timber. Destinations like the Grand Canyon, Sedona, Glen Canyon, Oak Creek, Canyon de Chelly, and the National Forests surrounding Flagstaff brought droves of tourists to northern Arizona to relish the region’s natural beauty.

——

[Flagstaff, Arizona. 1950. Fronske Studio. Fronske Studio Collection. NAU.PC.85.3.1.16.]

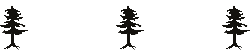

National Parks were initially designed with the railroad traveler in mind, making them easily accessible to the public. Into the 1950s, many tourists found these parks to be overcrowded with the increasing numbers of travelers on trains and automobiles. This led to the popularization of National Forests as tourism destinations.

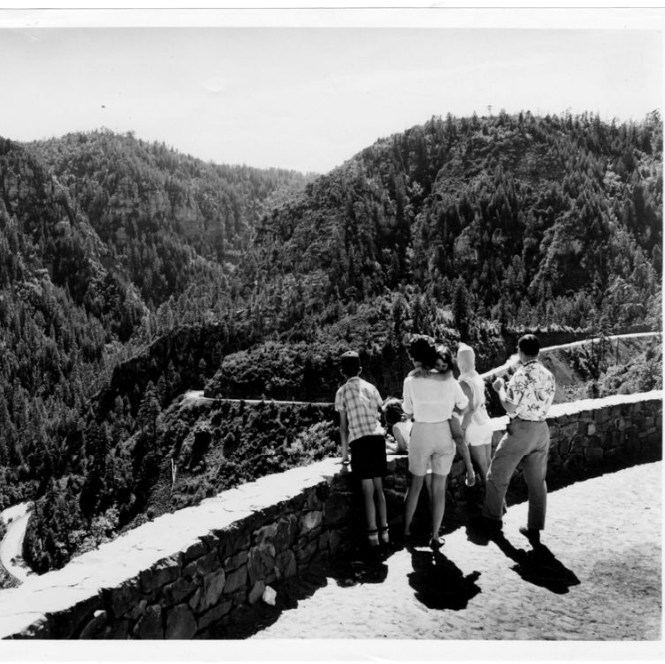

Forest Service roads were not accessible by train, and required an automobile or a dedicated backpacker to access remote portions of the National Forests. Vehicles could access paved roads, dirt roads, and even traverse across rough terrains. The ability to escape into more remote areas of the wilderness created a sense of freedom and privacy for automobile tourists, elevating the overall experience of the outdoors.

Automobile tourism provided increased accessibility to the wilderness, inspiring a revival in the romanticization and overall appreciation of the nation’s wilderness areas. These travelers followed in the footsteps of nineteenth-century nature writers like John Muir and Henry David Thoreau, who wrote about the importance of the environment and the human connection to the natural world; a movement known as romanticism.

This renewed environmental appreciation led to a growing number of American environmentalists, who would advocate for the protection of the aesthetic value of the nation’s wilderness areas during the 1950s and 1960s. Wilderness preservation groups such as the Sierra Club and the Nature Conservancy saw increased membership and activity through lobbying, organizing, rallying and petitioning against civil projects that diminished the natural beauty of wilderness areas.

Not only did roads facilitate tourism to the Flagstaff area, but they also added convenience and efficiency for Flagstaff’s lumber industry. Forest Service and Civilian Conservation Corps roads soon replaced railroad spurs throughout the woods. These roads provided easier access into portions of the forests where logging trains previously could not go, allowing logging crews to harvest more old-growth timber than before.

The Flagstaff lumber mill, Southwest Forest Industries, sparked controversy when they announced their long-term plan to remove old-growth ponderosa pine trees from the forests through an operation called “even-aged forest management.” This project sought to promote equal yields of timber and fulfill the demand for large saw timber. Flagstaff locals criticized that the lumber industry was turning their woods into a tree farm. To evade public scrutiny, Southwest Forest Industries and the Forest Service moved their logging operations out of sight from highways and major tourist areas.

——

[Martha McNary Chilcote. “Men working alongside the logging truck”. 1940-1950. NAU.PH.648.74.]