Route 66: A History

Branding the Southwest

As highway conditions improved in the 1920s, an increasing number of Americans ventured away from the railways and out onto the open road. Arizona, formerly an inconvenient obstacle on the way to California, became a destination in itself. Between 1945 and 1960, Arizona's population grew by as much as 75%. Tourists from the east filled up their tanks and followed Route 66 into Arizona to see natural wonders like the Grand Canyon, the Painted Desert, the Petrified Forest, and Meteor Crater — as well as the less majestic, human-made attractions that lined the highway.

Fred Harvey Hotel Billboard

English-born immigrant Fred Harvey recognized the Southwest’s economic potential early on and established his popular Harvey Houses along the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway routes in the late 1800s. As automobile travel gradually surpassed train travel, "railroad towns" became "highway towns," and the Fred Harvey Company adapted to fit the interests of the new tourists by offering off-road tours and access to Native American arts and entertainment. Hunter Clarkson's CourierCars Indian Detours similarly capitalized on travelers' fascination with Native American culture and thirst to experience the "real" Southwest. A 1936 Courier Cars Indian Detour brochure promised to introduce patrons to the "lure of the Far Southwest" (Fred Harvey Southwest Indian Detours 5) and stated: "The friendships of our couriers with representative Indians will open their picturesque homes to us as honored guests and also we shall see throughout its primitive manufacture the black pottery of San Ildefonso"

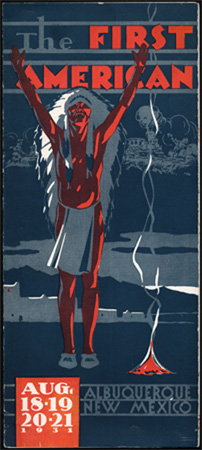

The contrived, romanticized version of the Southwest that tourists saw in guided tours, travel brochures, and road side attractions often had little in common with the reality of the region. Peter Dedek notes:

| Neon road signs featuring 'wild' Indians in feathered headdresses or cowboys in ten-gallon hats twirling lassos and thematic commercial architecture featuring faux adobe stucco walls adorned with nonfunctioning vigas and canles or concrete cones painted up to look like Indian teepees had more impact on the immediate roadside landscape than did authentic cultural landmarks, which were often located in inconvenient places a distance from the highway (Dedek 4). |

Racial stereotypes thrived along Route 66. Stoic Indian chiefs in elaborate costumes, sleepy Mexican hombres leaning against cacti, and noble white cowboys astride bucking broncos appeared on signs and served as mascots for many establishments. Business owners along Route 66 borrowed plentifully from Native American and Mexican imagery, erecting concrete teepees, plywood buffaloes, and oversized katsina dolls to entice tourists from the road. Souvenir shops, fashioning themselves after the trading posts of the Old West, hawked turquoise jewelry, Navajo rugs, and non-functional, mass produced replicas of Native American pottery.

The Native tribes whose crafts and images brought in tourist dollars did not necessarily benefit from the commercialization of their culture. Michael Wallis, author of Route 66: The Mother Road, emphasized the exploitative side of Route 66 in a speech to the Second Annual International Route 66 Roadie Gathering in Tucumcari, New Mexico: "As a boy I saw the 'no colored' signs at gas stations on my Route 66. … I also saw signs declaring 'No dogs, no Indians,' and only yards away a Native American craftsman sold his hand-fashioned art on the sidewalk" (quoted Dedek 80).

The First American

To many white, middle- and upper-class travelers, Route 66 symbolized the most positive aspects of American society – freedom, progress, and economic possibility -- but to the minorities who encountered racism, prejudice, and exploitation along the road, Route 66 embodied a much darker version of American history.

Alignments and Road Improvements

Alignments and Road Improvements