Route 66: A History

Good Roads Movement

As public demand for automobiles increased in the early 1900s, so did the desire for more reliable, standardized roads; if Americans were going to keep purchasing cars, they needed somewhere to drive them. Bicyclists and automobile owners joined together to advocate for improved road conditions nationwide -- a cause that came to be known as the Good Roads Movement. Organizations, including the Women’s National Trail Association and the Old Trails Association, began lobbying for an "Ocean-to-Ocean Highway" (Krim 52) -- a paved road, safer than the old wagon trails, that would allow the new wave of driving tourists to indulge their desire for a more individualized, leisurely form of travel. The National Old Trails Road Association formed in 1912 and proposed the "National Old Trails Road," which would connect Washington, DC and San Diego and ultimately become the southwestern stretch of Route 66.

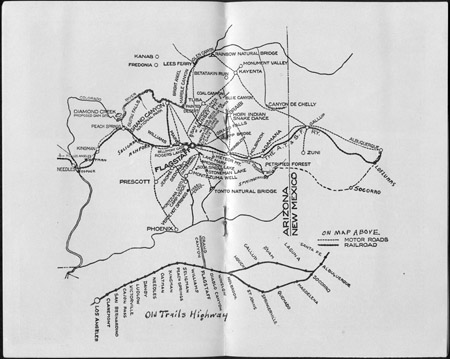

Map of the Old Trails Highway through Arizona, mid-1920s.

| Under the Federal Highway Act of 1921, the disorganized tangle of highways that had been in construction since the previous decade were mapped and equipped with consistent signage. Associated Highways Association President Cyrus Avery, a vocal proponent of the uniform highway system, pushed for a major east-west road to run through his hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Avery originally wanted his Chicago-to-Los Angeles road to be numbered 60, but lost the title to another major highway connecting Newport News, Virginia to Springfield, Missouri. From a small pool of remaining numbers, Avery and his allies chose the catchy, alliterative "66." The new U.S. 66 shields appeared early in Arizona, with signs erected through Winslow, Seligman, and Kingman (Krim 70) a month before the highway’s official commissioning. On November 11, 1926, a vote from Congress finalized the highway numbering system, and Route 66 was born. |  Portrait of Father Cyprian Vabre, Catholic Priest, originally from France; an early supporter of the "good roads" intitiative in northern Arizona. |

The federal number designation put U.S. Highway 66 on the map but did not necessarily improve its conditions; some of the more remote stretches remained unpaved until the mid-1930s. Still, the uniform numbering system "brought geographic cohesion and economic prosperity to the disparate regions of the country. ... Route 66 linked the isolated and predominantly rural West to the densely populated urban Midwest and Northeast." (National Park Service 3) The steady flow of tourists traveling down Route 66 bolstered the economies of small, previously isolated towns.

Ancient Paths and Railways

Ancient Paths and Railways